“Paraguay needs quality infrastructure”:

Viviana Pozzoli speaks on the country’s housing problem and shares her goals for the new year

Paraguayan architect Viviana Pozzoli has big dreams for her prolific Asunción-based studio Equipo de Arquitectura. In this interview, the DIVIA Award 2023 nominee tells Veronika Lukashevich about her dream of building within the public realm, making architecture that responds to global issues, and having a network of inspiring women in the industry

Viviana Pozzoli likes to be prepared. As we meet over Skype in early January, she logs in a few minutes early with a neatly placed notebook by her side. In it, she has jotted down a few paragraphs to help organize her thoughts. She greets me warmly from her studio, Equipo de Arquitectura, in Paraguayan capital Asunción. The days start rather late at Pozzoli’s office, with others typically arriving around ten or eleven in the morning. At 9 am, we have about an hour or two to speak undisturbed. “We are very flexible with the time here,” she says with a laugh, and I am curious: what does a typical day look like for her?

“I’ll show you,” she says, turning her computer screen around. I immediately notice the morning light beautifully dancing on the terracotta-colored walls—a testament to her studio’s reputation for prioritizing light in their designs. The screen reveals a table with a stack of intriguing book choices arranged on top, including The Singularity is Near by Ray Kurzweil, a 2005 publication about the future of humanity and the rise of artificial intelligence.

“AI is something everybody should be interested in because it is a part of our daily life and will drastically change the future of humanity,” she says as I ask her about her literary interests. The other books—La rebelíon de las masas (The Revolt of the Masses) by José Ortega y Gasset and Urban Structures for the future by Justus Dahinden—display her interests in philosophy, literature, and unbuilt architecture. “We are fascinated by utopian/dystopian architecture and urbanism.” (Fun fact: she and her team have a second Instagram account titled Unbuilt Architecture (@arquitecturanoconstruida), where they publish projects throughout history that were never realized.)

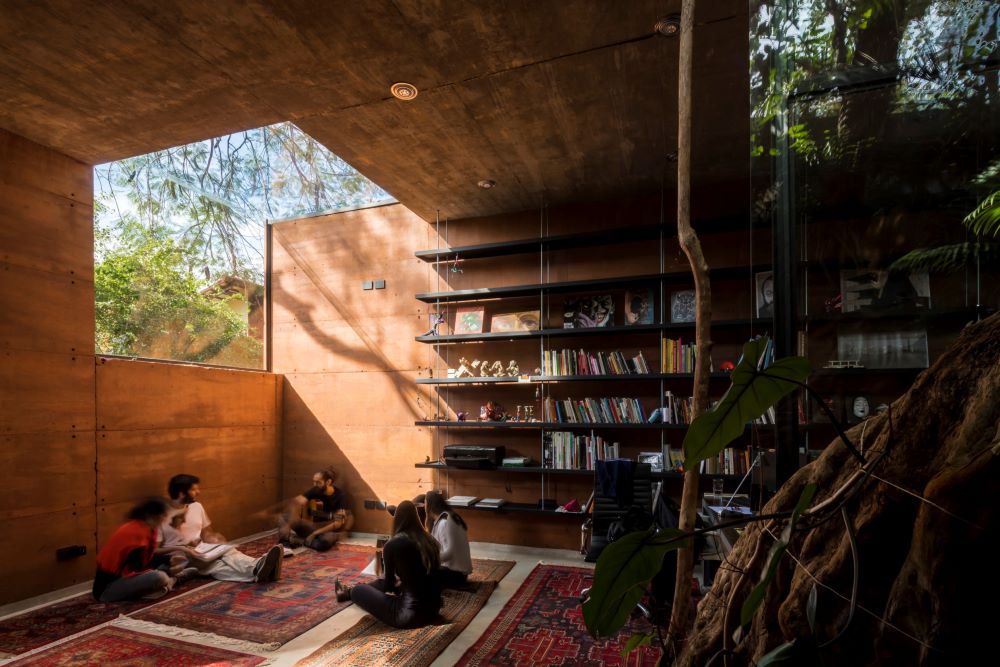

Pozzoli co-founded Equipo de Arquitectura with her partner (now husband) and Chilean-born architect, Horacio Cherniavsky, in 2017. The cube-shaped building, also called “Caja de Tierra” (Earth Box), was constructed using rammed earth, recycled glass, and formwork wood. It is designed around two existing trees (a signature move in their approach to work around and not against nature): the sneak, positioned outside but framed within the structure, and the guavirá, located in the middle of the space. Step into the 485-square-foot studio and you are likely to be greeted by jazz tunes playing in the background, occasionally interrupted by the purrs of Pozzoli’s rescue cat, Poe—named in honor of Edgar Allan Poe—, while her dog Linda, also a rescue, happily wags its tail somewhere nearby. Equipo de Arquitectura translates from Spanish to team of architecture, which perfectly captures the collaborative and relaxed atmosphere within the office. The team currently consists of four core members, but there are plans to expand this year. “We all get involved. When I have to make a decision, I have to share it with the others. Knowing that the others don’t support my idea—I don’t feel good doing that. We like to work in a horizontal way.”

Pozzoli and Cherniavsky met at university and started off their journey by competing in national competitions in 2017. With a plethora of options to choose from that year, they secured victories in two competitions which saw the restoration of an old construction that was used as a Synagogue for the Hebraic Union of Paraguay (2019) and the ASA Steam, a new school pavilion designed within the large campus of the American School of Asunción in Paraguay (2020). The prize money from the competitions was invested in the construction of their office. In just six-plus years, Equipo de Arquitectura have established a successful reputation in Paraguay and cultivated a decent network within the industry. They have engaged in a total of 30 projects, 13 of which, including schools, offices, and residential houses, have been successfully realized.

Their work has garnered recognition from prominent architects in the country, including Javier Corvalán, who co-designed one of the ten Vatican chapels in San Giorgio Maggiore for the 2018 Architecture Biennale. His influence on Pozzoli’s strong use of daylight and air is evident in her approach (she worked in Corvalán’s office in 2014 and 2015; he was also her thesis project tutor at university). Martin Jasper, the founder of Jasper Architects operating across Berlin, Buenos Aires, and Asunción, nominated Pozzoli for the inaugural international DIVIA Award in 2023. This recognition was initiated by Diversity in Architecture, a Berlin-based organization providing a platform for exceptional women in architecture who are committed to addressing the environmental and social challenges of our modern world.

“Viviana Pozzoli’s architectural works embody an honest simplicity that sets them apart,” says Martin Jasper, who served as DIVIA’s Advisory Board member for South America. “The artful fusion of local traditional building techniques distinguishes her work; brick and earth are seamlessly transformed into contemporary masterpieces. Her creations [showcase] a complete architecture that encompasses ecology, materiality, and groundbreaking research—a testament to her commitment to both heritage and innovation.”

Pozzoli’s ambition and prolific output in such a short period of time are so impressive that it’s hard to believe her family weren’t initially too keen on her becoming an architect. “My father said to me: you will die poor,” she recalls. A civil engineer, he encountered many challenges during the economic crisis in Paraguay in the mid-nineties. But the times have changed. While Paraguay remains one of the poorest countries in South America, the past decade has witnessed an economic upswing, providing Pozzoli and her university peers with plenty of work opportunities. “Paraguay used to be incognito but then many architecture students came here to do internships with Javier Corvalán and other studios and stayed,” she says. Besides, the inspiration to become an architect had been instilled in her long before she was old enough to consciously choose a career path. Her mother, who took a break from education to marry and have children, had plans to resume her studies later but an unforeseen illness prevented her from pursuing this goal. “My grandmother always wanted her daughter to be a professional because in her time it had been impossible. So, I grew [up] with that idea that being an architect was something that my mother wanted—but at the time I didn’t know what it meant.”

“We need a lot of infrastructure here, but a quality one, because in my country the government is never interested in developing projects with architectural quality.”

Although strongly influenced by this personal experience, the career choice wasn’t that far-fetched considering that already as a child, Pozzoli showed an interest in spaces. “I have many memories in my youth about atmosphere, colors, temperature, textures. I think I’ve always been attracted to the feeling that places, materials, smells, and light transmit,” she reflects. “As soon as I realized that everything that had attracted me subconsciously was a world of meaning and a logical explanation, my passion grew. I feel very grateful for architecture. It opens your mind to a world of abstraction and ideas and at the same time of emotions and feelings.”

A lot of that passion is poured into her projects, one of them being a childcare center in the suburb of the important port town Villeta, situated on the banks of the Paraguay River on the border to Argentina. It was completed in 2021 and gained international attention early last year when Viviana Pozzoli was awarded with the Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture, run in association with the Architectural Review. The design considers input from teachers specializing in Reggio Emilia and Montessori methodologies and focuses on aspects such as “textures, the sensory experience of the spaces, and their effect on children.”

The center strays away from the enclosed concept of an educational space and opens up the walls to enable a dialogue with nature. The square-shaped building is divided into four large sections, all connected through outdoor spaces and with their own separate patios. The central courtyard functions as a playground. The four sections make up two large classrooms that can be further divided into two smaller spaces, a dining, and an administrative area. Green roofs, cross ventilation, and the use of rammed earth were intentional choices to minimize environmental impact and ensure comfort for users. The experience working on the childcare center held numerous lessons for Pozzoli, and one of them even altered her perception of sustainability—but not in the way one might expect.

“Sheila O’Donnell [architect and judge of the Moira Gemmill Prize for Emerging Architecture] gave me a revelation,” says Pozzoli and shares the story behind it.

Paraguay’s Minister of Education requested Equipo de Arquitectura’s design from the client in order to replicate it throughout the country. Pozzoli recalls the initial skepticism within her team: “The circumstance was totally atypical. We were like, this is not good, nobody called us; they don’t recognize the value of the architect in this.” Eventually, her team agreed to donate the design hoping to prevent the use of a subpar alternative and offered the government their architectural guidance on the design’s adaptation to various sites. Disappointingly, the call never came.

“Two years and a pandemic later I found out that the government built 19 childcare centers across the country using our design—rammed earth walls, green roofs, cross ventilation…We couldn’t believe it. But then Sheila said to me, ‘That too is sustainability because the project could be built without the architect.’ And I didn’t see it that way [at first], but now I understand.”

While the situation could have been handled differently, and, let’s face it, more tactfully, it is not entirely surprising that their design was selected, considering Equipo de Arquitectura’s strong responsiveness to the local climate and context. Pozzoli’s practice embraces different realities, materials, programs, and scales, which, she says, ultimately reflects her personal understanding of diversity. “Diversity is also richness because it allows me to expand my vision of the world, of the different realities, where by knowing and learning and seeing how to collaborate together, we can expand the spectrum of possibilities and opportunities.”

“Social housing needs to be mixed use. We have to co-exist in a diverse way—economically and socially.”

In the future, she plans on shifting her impact onto the public realm: “Public projects are my goal. That would be a dream.” The first issue she would tackle if given a chance? “The social housing problem. We need a lot of infrastructure here, but [a] quality one, because in my country the government is never interested in developing projects with architectural quality. Many times, the government wastes opportunities and resources on mediocre projects that do not help to resolve the social and environmental problems.”

Here she refers to the remote, single-use buildings far away from the city center and the lack of infrastructure to reach them. According to Habitat for Humanity, 20% of the families in Asunción live in informal settlements without access to basic services. In recent years, Paraguay’s government has tripled investment in social housing, but according to Pozzoli, the quality of the buildings leaves much to be desired. “Social housing needs to be mixed use. We have to co-exist in a diverse way—economically and socially.”

Though visibly frustrated, Pozzoli is determined to find appropriate solutions to the problem, despite facing a whole new set of challenges along the way. While she has been involved in public projects before, her role has always been secondary. This is mainly due, she says, to the stringent conditions set by the banks for the projects funded through loans. The bank typically demands highly qualified academic and professional resumes from architects—a criterion that Pozzoli has been unable to fully fulfil thus far, despite dedicating half of her time to academic work.

She serves as project professor at her alma mater, the private Universidad Católica Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, and as assistant professor at the Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Arte de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción. “It [takes up] a lot of time, but it’s the only way I can contribute to a new generation,” she says. This past semester Pozzoli welcomed the very first Guaraní indigenous woman studying architecture in Paraguay and dedicated a class to understanding the Guaraní community. “We worked on the projects there, [the student] also gave us guidelines about her culture and her contexts. It was a very rich experience,” says Pozzoli.

“Diversity is also richness because it allows me to expand my vision of the world, of the different realities, where by knowing and learning and seeing how to collaborate together, we can expand the spectrum of possibilities and opportunities.”

With her work, Pozzoli wants to empower women in the field, noting that the importance of gender equality is still not fully acknowledged among the older male architects in Paraguay. “In the National University, I’m in the first semester where the main professor is a woman—Cecilia Roman is the only woman who heads an architectural design course in our studio unit.” Pozzoli further expresses her admiration for female leaders in her industry, citing Marta Maccaglia, a fellow nominee and the winner of the DIVIA Award 2023, as her inspiration. “I am fascinated by what she’s doing because it’s incredible. She has a very big personality and is very confident, and that’s a thing that I really admire.” Maccaglia and her architectural NGO Semillas build schools and other educational institutions in the Peruvian jungle. Pozzoli’s role models also include the Mexican practitioner Gabriela Carrillo, whom she calls “a rock star” for her social impact work, her peer Violeta Pérez, and Brazilian architect Cristiane Muniz. “I try to maintain those kinds of figures very close to me in order to get strength from them,” says Pozzoli.

It appears she might seek their support more than usual this year, as 2024 looks bright and busy for the 33-year-old. Pozzoli is ready to make the next step and “grow academically”, preferably in the States. Her plan is to check all the boxes on her résumé in order to be hired in a leading role for architectural projects in the public sphere. Her partner has already been granted a scholarship (Fulbright), so she is even more determined to receive one herself. “It’s my turn now,” she says, smiling. Then there are her architectural commitments. Among the projects in development are a private house for a European family located in the jungle near the southern city of Encarnación, as well as a conversion of a historic villa and an industrial building into offices. There is also social housing planned for families in the Chacarita Alta neighborhood, a historical area near the river prone to flooding. Pozzoli’s studio has collaborated with Adamo Faiden from Buenos Aires and MOS Architects from New York on this project, which is scheduled for construction this year.

“We should be aware about the global difficulties that humankind is going through. If we make architecture respond to those conditions, then I think we can speak of a contribution towards a better society and world.”

Any advice she’d give herself or any other young architect facing a busy year ahead filled with uncertainty and important choices? Turning to her notebook, Pozzoli begins to read a paragraph she had written down ahead of the interview:

“Confidence. We have to trust in our capacities and remember that each of us has a unique and valuable way of being in architecture. Passion in what we do is the key to success. It makes the difficulties much lighter and the satisfaction more full.” She flips a page, then continues: “Each context has its problems and a specific crisis to resolve. At the same time, we should be aware about the global difficulties that humankind is going through. If we make architecture respond to those conditions, then I think we can speak of a contribution towards a better society and world.”

Text: Veronika Lukashevich