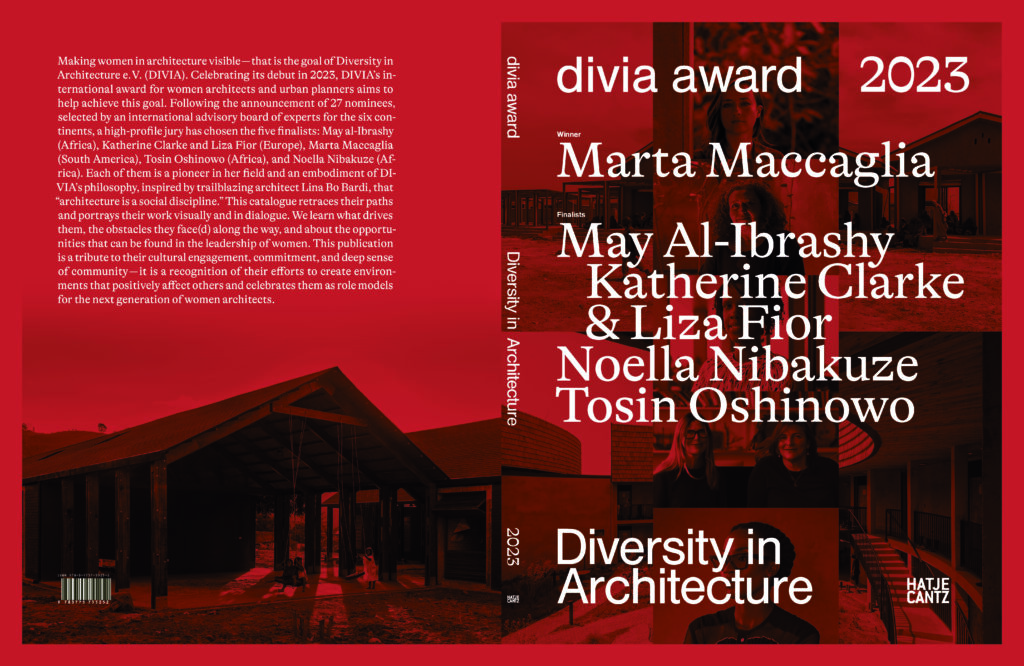

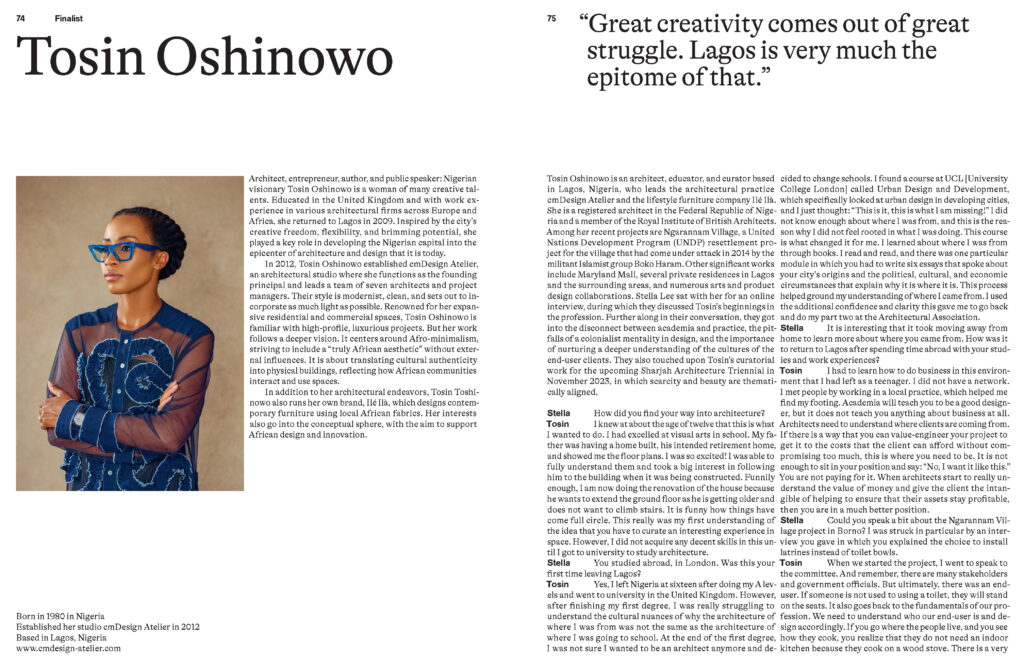

TOSIN OSHINOWO

on what we can learn from African architecture

After concluding the second edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial just over a month ago, architect and DIVIA Award 2023 finalist Tosin Oshinowo has stepped away from her practice for the first time in her career to join a fellowship in Italy. In this interview, she shares with Veronika Lukashevich her thoughts on what her future plans might entail.

Tosin Oshinowo is seated in her room with about an hour to spare. She’s been so busy lately that it’s been hard to keep track of her whereabouts. For our interview, I expected her to be in Lagos, Nigeria, where she is usually based. However, just a few days before our online appointment, she announced on her Instagram that she was actually in Italy.

In Bellagio, to be exact, on the shores of Lake Como. The scenery is idyllic, with deep blue waters set against the rocky alpine mountains—a perfect place to unwind and reset. But that’s not why she’s there. Tosin Oshinowo is currently residing at The Bellagio Center, an establishment under the auspices of the globally acclaimed Rockefeller Foundation, renowned for its philanthropic endeavors. She has recently become a fellow at this prestigious institution, describing her experience as akin to “an intellectual wellbeing retreat.” The program—which previously hosted trailblazers like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a staunch advocate for gender equality and the second woman to serve on the US. Supreme Court, and author and civil rights activist Maya Angelou—unites individuals across disciplines whose work aims to solve global issues. A friend who had completed the four-week residency thought Oshinowo would be the perfect candidate and encouraged her to apply. “I looked at it and I thought, ‘oh, I’ve never done anything like this’, which is to step away from my practice and say, ‘okay, I want to just focus on this’,” says Oshinowo. “So, it’s been very interesting taking this time out.”

The fellowship group consists of 15 mid-to-late-career participants who prioritize environmentalism in their work. Among them are a poet, several other writers, a former judge, and even a past employee of the Obama administration, as Oshinowo enthusiastically notes. The fellows reside in a beautiful neoclassical house, once owned by Ella Holbrook Walker, Princess of Torree e Tasso (related to the wealthy Walker family known for their whiskey distillery). In 1959, she donated her villa to the Rockefeller Foundation, wishing to support institutions that contribute to the wellbeing of humanity. “She wanted her legacy to live on after she was gone,” says Oshinowo.

“I have given so much, it’s such a massive buildup, and it’s almost like you put all this water into this big container, and then you open it up and it just goes ‘whoosh’.”

The fellows are well taken care of, enjoying access to private studios, a 50-acre-park, and even two sessions with an osteopath (talk about a high-quality retreat!). While there is a strong emphasis on individual work, which must be presented at the end of their stay, lively conversations naturally occur during dinners and lunches. “I have been very inspired by the stories that I’ve heard so far and the experiences of my fellow cohorts,” says Oshinowo. “But it might be one of those things that matures much later, when you start to reflect on the experiences of being in a place like this.”

It seems that the fellowship couldn’t have come at a better time, allowing Oshinowo to step back and reflect on the whirlwind of the past few months. In March, she completed the second edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial in the United Arab Emirates, a project she curated and worked on for 33 months. Running from November 11, 2023, through March 10, 2024, under the theme The Beauty of Impermanence: An Architecture of Adaptability, the Triennial focused on amplifying voices often overlooked in international dialogues, particularly from the Global South. (The first edition took place in 2019 and was curated by Adrian Lahoud under the theme Rights of Future Generations). The exhibition showcased contributions from 29 architects and studios representing 26 countries, largely centered on strategies of reuse and architecture created with scarce resources. All participants were shaped by some form of “duality,” as Oshinowo explains, meaning they’ve lived and/or worked in multicultural settings. “They have a visibility that is very powerful because they have a hybridized reality and perspective,” she says. “By being in this elevated position, they can pull these very valuable narratives that I believe are very important to our current climate crisis.”

Some of the selected projects include a building made of pink Himalayan salt by Ethiopian designer Miriam Hillawi Abraham, which directly relates to the Triennial’s themes of scarcity and impermanence. Named The Museum of Artifice (the photos below were taken by Danko Stjepanovic), it pays tribute to Ethiopia’s rock-hewn Lalibela churches and the abandoned village of Dallol, situated in one of the hottest places on the planet: the Danakil Depression. Dallol still features single-storey buildings made of mortar bonded salt blocks sourced from the adjacent salt lakes.

Another standout project is We Rest at the Bird’s Nest, a three-story building made of scaffolding and organic waste by the Nigerian architects Papa Omotayo and Eve Nnaji. Inspired by the potted plants and bird cages tended to by mechanics in an industrial area in Sharjah, the architects were the only participants who chose to focus on ecology. Their building served as a refuge for both birds and workers in an area that typically wouldn’t attract wildlife. “It was very interesting to see how these two took a subject matter that nobody considered,” says Oshinowo. “Very rarely will you have an architect design for animals.”

During her time curating the Triennial, Oshinowo gained profound insights into her culture and underwent significant personal growth. With the Triennial consuming so much of her energy, requiring immense physical and mental presence, I wonder how she felt the moment it ended.

“I felt quite deflated,” she admits. “I have given so much, it’s such a massive buildup, and it’s almost like you put all this water into this big container, and then you open it up and it just goes ‘whoosh’—here she gestures with her hands to illustrate an explosion—, and you just see how far the water is going to percolate onto the surface below. And that’s how it feels.”

Some of the ideas that blossomed from this experience have already taken root. This past year was marked by changes and introspective reflections that challenged Oshinowo more than ever before, particularly concerning her values in relation to consumption.

“A lot of the things that we consume, we actually do not need,” she begins. “Yes, so much of capitalism has informed our urban environments and will continue to do so. But I think once you realize that it is both the benefactor and the problem—the amount of waste it produces and the realization that it’s an ideology that is brainwashing—the magic of it is removed. And I feel very much in that position right now.”

She goes on to explain how the convenience of hyper-consumerism often disregards its long-term impact on the planet, promoting an unsustainable, impractical, and often misguided notion of progress. She makes an example.

“The simple fact as air conditioning—we don’t need it in Nigeria. You have people wearing clothes that are completely inappropriate for the environment because it’s seen as aspirational and now comfortable because of air-conditioning. It is so lifestyle driven that anything about practicality is completely negated for this attainment. Architecture plays a role in it, but it is only one part of a multi-player process.”

Oshinowo is pragmatic enough to recognize that she must operate within this reality to enact lasting change. “I’m not saying I’m going to go live completely separate from modernity,” she grins, “but I have to find, very consciously and very responsibly, ways to balance ecology with my capitalist reality. It’s systemic change that we need, and, you know, there are a lot of things to consider, but first and foremost, it starts with an awareness.”

Born in Lagos, Oshinowo tells me she grew up amidst scarcity but only realized this during her training in the UK (she received her Diploma at the Architectural Association in London), an education she describes as rooted in the concept of surplus. “We never thought about where the materials were coming from, we just specified and designed things, but never within the understanding that it was part of a process,” she explains. Upon returning to Nigeria and establishing her practice in 2013, Oshinowo found herself unable to directly apply these learned principles in her local context. This initial frustration evolved into a recognition that limitations offered opportunities for innovation. This mindset guided her exploration of the topic within the framework of the modern city for the Triennial.

“I’m interested in how some of our African traditions, materials, and our former ways of building could combat climate change,” she says. “There is a very interesting phenomenon that is happening across a lot of African cities, where, because they were master planned using orthodox planning methodologies, they should no longer function, [but they do]. [This is thanks to the] self-organizing, indigenous systems like informal markets that are almost organic forms of being. What can we learn from these adaptations to scarcity that exist here that could potentially benefit a global conversation and hopefully reduce our run on our natural resources?” She pauses as if awaiting my response.

“Do you have an answer for that?” I ask her.

“That’s why I’m here,” she laughs, looking around her room at the Bellagio Center.

Oshinowo is contemplating turning her fellowship research into a book, although she concedes that the project could manifest in various ways. “Whatever this materializes into, I hope to take that conversation further and say: Can we create an urban reality that is appropriate for our context? [I’m aware of] the big inequities that exist between the regions, this idea of extraction from one region to benefit another, and how the regions that benefited have formed a reference and canon to which we all abide. We’ve always tried to invite an infrastructure or a system that doesn’t work in our [African] context, so, in a way, we need to unlearn to relearn.”

“A lot of the things that we consume, we actually do not need. Once you realize that [capitalism] is both the benefactor and the problem—the amount of waste it produces and the realization that it’s an ideology that is brainwashing—the magic of it is removed.”

While her current focus lies on her research, Tosin Oshinowo has other exciting commitments awaiting her this year. Upon her return to Lagos, she will continue her projects for Goethe Institut and other private commissions. In May, she will travel to Australia to participate in a panel and deliver a keynote speech at the Melbourne Design Week. There have also been some changes in her practice. After a decade, she recently rebranded it as Ọshinówò Studio, explaining that the original name, cmDesign Atelier, was selected at the time to project a more established image. “As a woman and a young practitioner, you’re faced not just with ageism, but with sexism. I’d wanted to ensure that I created the notion of establishment that people would be confident to give us work. Maybe if I had started with [my] name from the beginning, it would not be where it is now.”

Mindful of her role as a role model and a woman in the public eye, Oshinowo feels honored to be a member of DIVIA. “Representation is important. When people see people who look like them, then they know that [success in this industry] is possible. This idea of excellence can be obtained. This idea of progress is within your reach. When we have more figures who are celebrated and able to continue to pivot from that celebration, I think then we’re getting closer to a really equitable world,” she says, then adds quickly: “We are not there at all. But by having more platforms like DIVIA, we are at least moving in a positive direction, which is why I am very happy to be associated with it.”

Tosin Oshinowo was nominated for the inaugural DIVIA Award 2023 by Otobong Nkanga, a critically acclaimed artist, fellow Nigerian, and DIVIA’s Advisory Board member for Africa. Among 27 international nominees, Oshinowo was selected as one of the five finalists by a high-profile jury that included Martha Thorne, former executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The jury praised Oshinowo’s “diversity of modes of engagement” and the “wide range of activities that she has embraced under the umbrella of architecture as a way of serving a broad array of constituencies in society.” In February, Oshinowo gave a final presentation at Tübingen University as part of their collaboration with DIVIA, featuring a lecture series delivered by the DIVIA Award finalists. During the lecture, she discussed her latest work and her long-term motivations as an architect. Like Ella Holbrook Walker, Oshinowo is motivated by legacy. She seeks to leave a positive imprint on the world, not only for herself and her 13-year-old daughter but also for her community. “This weighs very heavily on my chest,” she says then grows thoughtful. “Can you imagine passing through the world and there was no acknowledgement that you were here? I think that’s a really sad notion.”