Rozana Montiel

on “the active gaze,” launching a cultural space, and the importance of awards

From paving the way for women to merging art with design and teaching at prestigious universities—Rozana Montiel is that name in architecture that you can’t and don’t want to overlook. As she takes time this year to reflect upon her career, she spoke to Veronika Lukashevich about her beginnings in architecture, how art and cinema have impacted her thinking, and the new cultural space she opens in July

There is a scene in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up where the fashion photographer Thomas, played by David Hemmings, is examining a series of photographs he took in a park. When he notices something odd in one of the pictures, he enlarges the section in question and discovers what appears to be a body lying in the grass and a man with a gun hiding in the bushes. The more he “blows the photos up,” however, the grainer and more abstract they become, making us question: is what he sees real or just the product of his imagination?

“That’s what I call activating your gaze,” says Rozana Montiel as we speak via Zoom, about a month after I visit her cozy, light-filled studio in Mexico City. “It’s about making the invisible visible, being creative and slowing your mind. It’s about imagining an impossible building first, then figuring out how to make it possible. After a while, it becomes a whole methodology, and serendipity starts to happen, because you are alert, right?”, she says as if awaiting my approval. “You have eyes everywhere.”

Rozana Montiel has always been intrigued by different ways of seeing; she looks for clues in other disciplines, which is why she names the film as one of the main influences on her architectural process. With every brief, she challenges herself to think outside the box and seek out the hidden nuances.

That is, in fact, how she was raised. Both of her parents were art collectors, and her childhood home was a hub of creativity. Her father built a gallery inside their house, where friends would gather to admire works of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. Amid these notable male artists was a captivating piece by Spanish painter Remedios Varo, who took refuge in Mexico during the Second World War. “Varo painted these surreal and very imaginative works with beautiful stories,” Montiel says, calling Varo her inspiration. “It was as if we were connected.”

Montiel’s interest in the arts gradually transitioned to her love for spaces. When she was nine, she told her parents she wanted to design her own room. The result was so inviting that it became the go-to hangout spot for all her friends. “I was constantly changing it, creating, displacing, moving and doing something else with what I had,” she says.

“There’s not just one way of doing architecture, it’s not just laying bricks. I do architecture by constructing a whole new language.”

Her father noticed his daughter’s gifts and suggested that she study architecture to combine her love for art and design. It seemed like a reasonable idea, so she followed his advice and earned a degree in architecture and urban planning from the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico in 1998. Her passion for critical thinking then led her to pursue a master’s degree in architectural theory and criticism in Barcelona. During this period, Montiel fully immersed herself in her life abroad. She took advantage of the new environment to learn and broaden her mind by going to the cinema and museums. “I was also reading like crazy all day and learning Dada poetry recited by my teacher at a bar,” she adds.

Upon her return from Spain, Montiel joined forces with three female architects that she had met at university. Together, they gave lectures and worked on renovations, operating out of a small space in the back of a friend’s painting studio. “We were very proactive, it was our mentality,” she says. However, as the years passed, the team gradually dissolved, with some members starting families and others moving abroad. All of a sudden, Montiel was the only one left.

“Many women leave when they get pregnant. They stop working and then it’s difficult for them to come back,” she says empathetically. “Many of my friends were having kids in their early thirties, but I was not even married or had a partner then. So I was the only one who wanted to continue. It happened very organically.”

Embarking on this journey on her own was no easy feat, given the scarcity of studios led solely by women at the time. “There were many partnerships with men but just a woman leading—there were none. Then Tatiana Bilbao opened [her office], and step by step the number grew.”

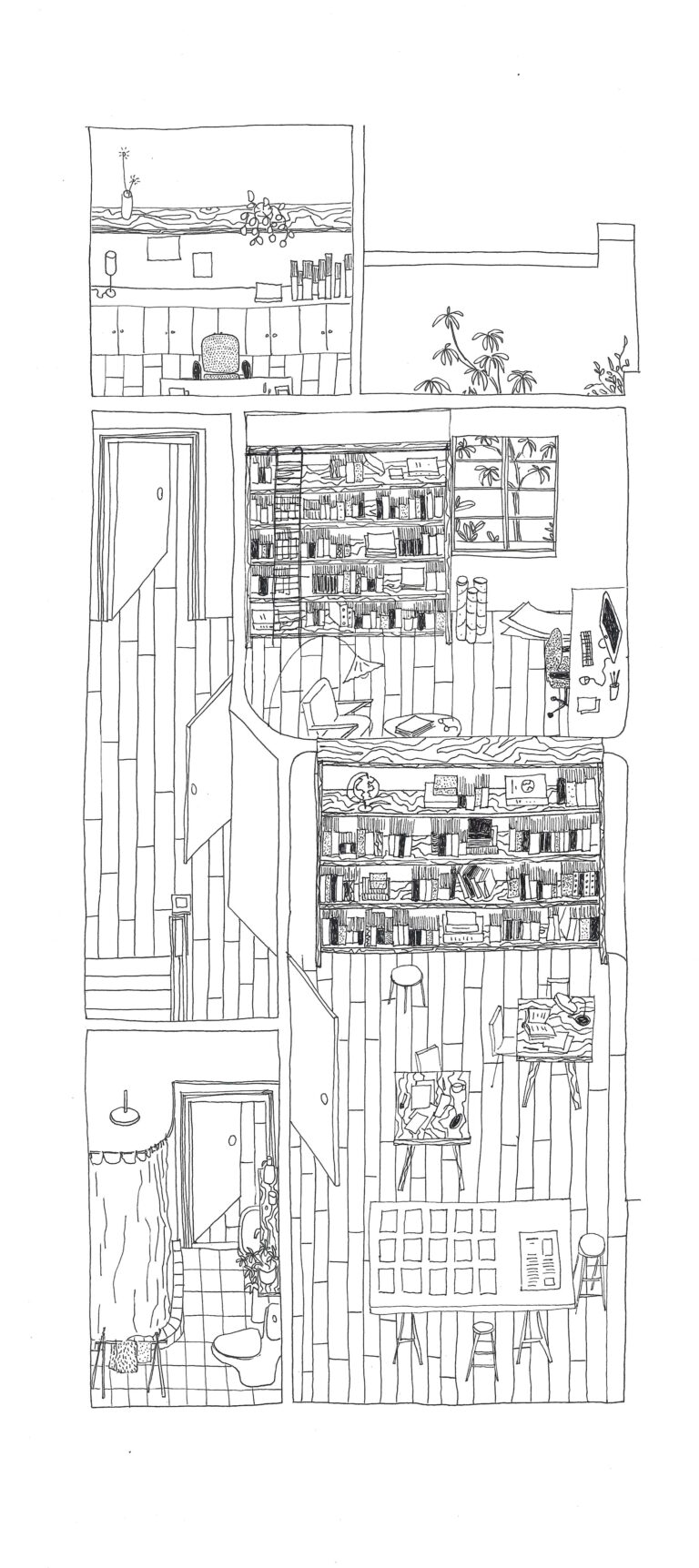

What gave Montiel the dedication to proceed? “It was difficult for me to find a studio where I could fit all my interests. I wanted more than designing and building; for me it was also about critical thinking, doing research, relating and blurring the boundaries with art. So when I couldn’t find anything, I thought, ‘why don’t I just do it myself?’”

And so she did. In 2009, she established her own architectural firm, Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, which has since undertaken an array of projects, from micro-objects to urban interventions. The beginning was challenging, however, as the men she worked with struggled to trust her professionally and acknowledge her independent success. This perception shifted as Montiel began receiving recognition and awards.

Back in 2001 she won the young creators grant called FONCA from the Mexican government. It is awarded annually to 100 young creators from all disciplines—architecture, cinema, sculpture, painting, music, choreography, writing—to develop a project over the course of a year. All 100 creators and their respective tutors travel together to various states in Mexico, using the time to interact and learn from each other. “It was a life-changing experience during which I developed a passion for researching the city and building artifacts from found materials,” Montiel says. “I met interesting creators; I still collaborate with many of them today.”

This achievement got the ball rolling. In 2010, she became the first woman to receive a three-year grant for artistic creators from the Mexican government (and just last year, she was the first woman to win the Luis Barragán award). For Montiel, being given this grant meant more than just winning; it paved the way for other women to gather the courage to apply, too. “A lot of women didn’t even know that it was a possibility for them,” she says, noting that previously, it was primarily older men who took advantage of the opportunity. “I think my generation was pushing the boundaries to open things in a different way. The generation now, they have their own set of problems to deal with, but opportunities are open to them a bit more.”

She then mentions that she appreciates how the DIVIA Award helps women establish themselves in the profession. “Awards like this provide the credentials for people to trust you,” she says. Montiel has supported DIVIA from the beginning, having written an article about one of her projects for Women in Architecture, edited by DIVIA Founder and Chair Dr. Ursula Schwitalla.

Reflecting upon her career over the last two decades, Montiel feels joyful and proud. “It’s been worth all the effort of not deciding to let it go all these years ago,” she says. Once she felt established enough, having worked diligently throughout her thirties, she was ready to start a family. “I had my daughter when I was almost 40, so I was able to focus on my work first.” She pauses, growing thoughtful. “Maybe planting the seed would have been more difficult while having a child.”

For a while, Montiel’s office was staffed only by women, which means her employees understood the demands of being a working mother. “It was an amazing energy. They were really helpful and embraced my daughter. It was beautiful to see.”

“Many women stop working when they get pregnant and then it’s difficult for them to come back. My friends were having kids in their early thirties, but I was not even married or had a partner then. So I was the only one who wanted to continue.”

It’s impossible to overlook the theme of empowered women in Montiel’s life and work, a fact that extends even to her workspace. Her new studio in Mexico City is situated on the first floor of the former residence of Mexican poet and painter Carmen Mondragón (1893-1978), mainly known as Nahui Olin. Initially unaware that Olin once occupied the building, Montiel recognized an opportunity when the previous tenant vacated the upper floor. She rented it with plans to transform it into a cultural space that “sets ideas in motion. “It felt like destiny,” she says. “Olin was progressive and believed in the rights of women, so I was happy to give her space its due justice.”

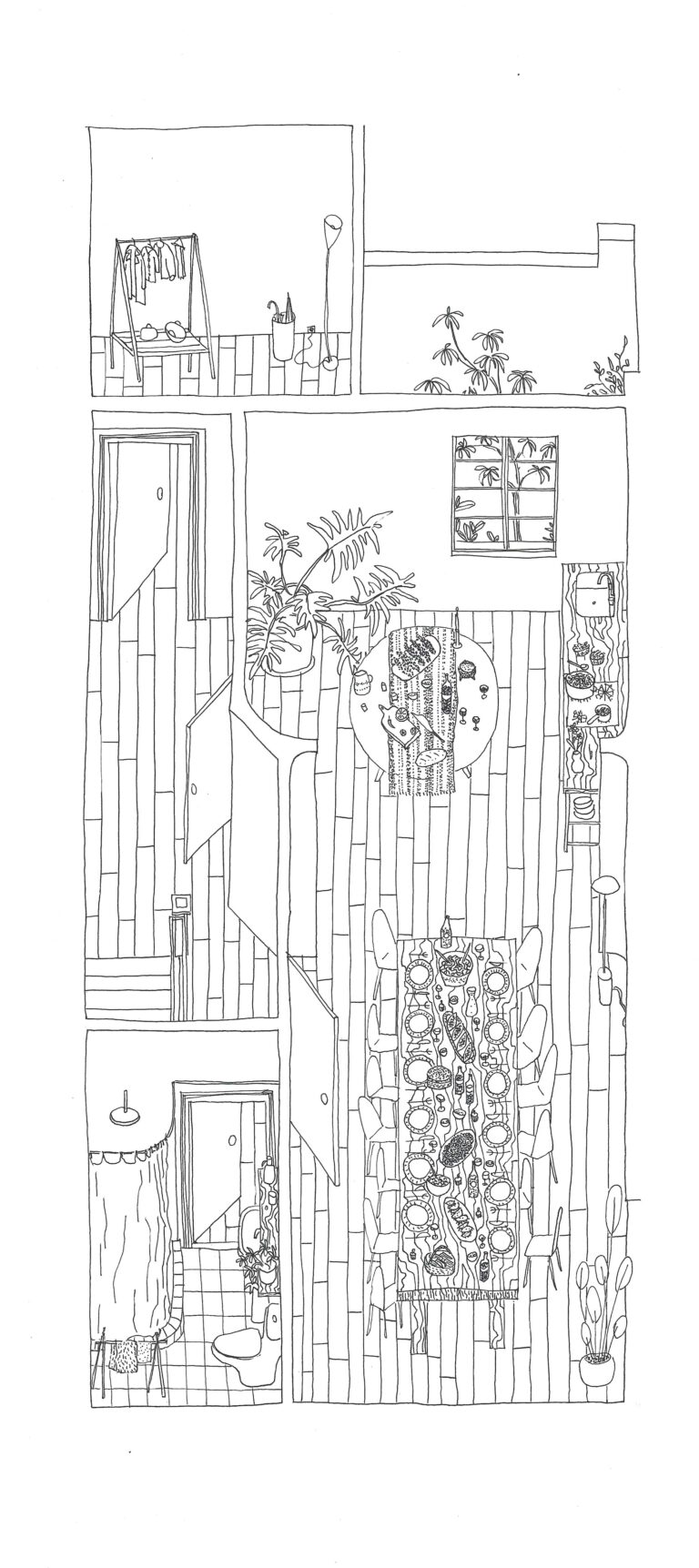

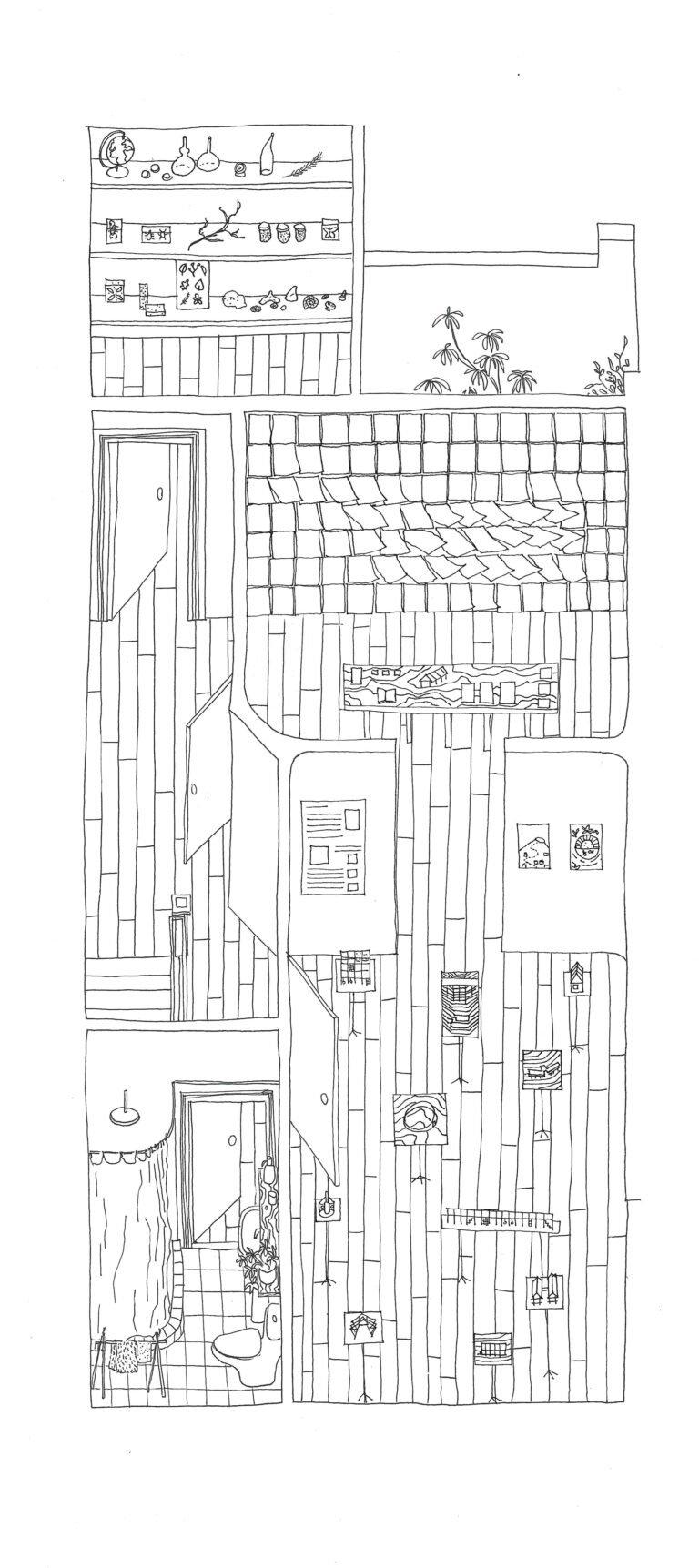

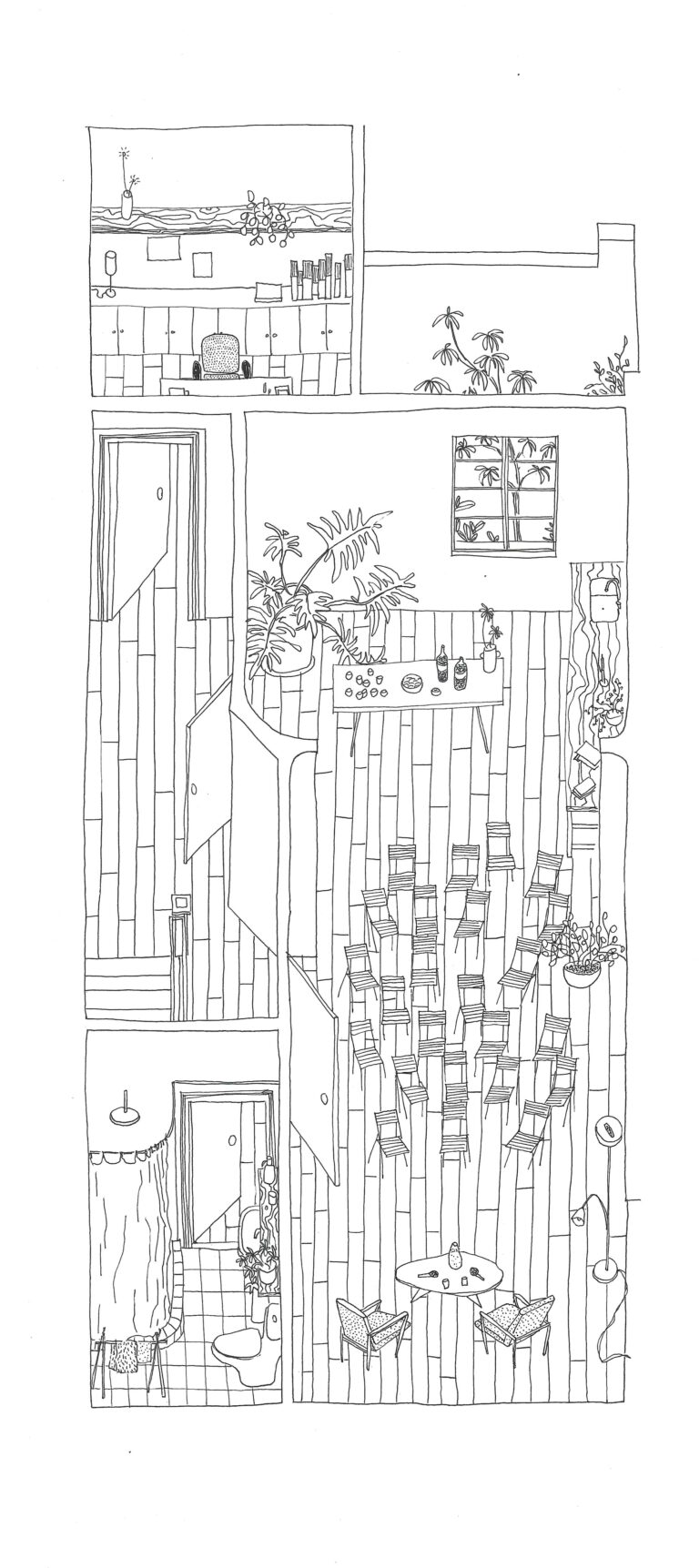

Named Calli Ollin (with ‘Calli’ meaning house in the Aztec language Nahuatl and ‘Ollin’ meaning movement), the place will serve as a hub for dialogue between architecture, design, and art. Each year, it will host workshops, exhibitions, discussions, and publications to encourage critical thinking about pressing global issues. “The space is about proactivity, addressing significant issues of our work not as problems but as opportunities for finding solutions,” Montiel explains.

The inaugural exhibition launching this July will honor Nahui Olin, presenting her not merely as the muse of painter Gerardo Murillo, also known as Dr. Atl, but as an artist and poet in her own right. “It will be a way of exploring the world through her eyes,” says Montiel, highlighting the parallel to her own approach of seeking diverse perspectives. The exhibition will feature Nahui Olin’s point of view and her enduring presence in her old home that she inherited from her father. The second exhibition, scheduled for later in the year, will delve into domesticity, focusing on her belongings and everyday life. The idea is to recreate the space she once inhabited and explore the themes she depicted in her paintings. The final two exhibitions will center on Olin’s writings, using her poems to illuminate her inner world, and on the body as her primary dwelling.

If it was not clear before, it certainly is now: Montiel sees architecture as more than just what meets the eye; to her, it has a philosophical, even scholarly foundation. “There’s not just one way of doing architecture, it’s not just laying bricks. I do architecture by constructing a whole new language,” she explains. I ask her if there is a project in her repertoire that perfectly encapsulates her values. It doesn’t take her long to come up with an answer. “Pilares,” she says with certainty.

“In this project, I aimed for simplicity in materials, a strong identity with minimal elements and colors. I also wanted to create small patios to connect nature with architecture and blur the barriers between the interior and the exterior,” she explains.

That she did master. Montiel was commissioned by the government to transform an unused, gated basketball court in Iztapalapa, one of Mexico City’s most densely populated neighborhoods, into a peaceful, public space. By removing the barriers and preserving two large trees, she created a space where people can gather, participate in activities, and relax. The project site is strategically located on a corner where a weekly street market takes place, fostering a natural flow of movement.

The layout integrates forums, sports facilities, and classrooms across two stories connected by landscaped patios and adaptable spaces. Striated walls are designed to interact with light and shadow, and concrete is creatively used throughout the architecture, appearing in lattices, ventilated interiors, and sustainable features such as rainwater collection systems, as well as energy-efficient lighting and faucets.

“It’s beautiful to see the energy that’s happening there. You feel safe, you feel comfortable, you feel at home,” says Montiel proud. “When you’re there, you forget about all the noise, and you feel like you’re in a cultural oasis.” One of the strategies to create this homely feeling was to paint the space in the color mauve, an unusual decision for a steel structure and one that Montiel had to fight for. “Even the government had to approve it first,” she laughs.

Apart from her studio work, Montiel also dedicates a significant amount of her time to academia. Over the years, she has taught at some of the most prestigious universities in the world, including Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico, as well as Cornell, Columbia, and Berkeley in the United States. “It’s been an important part of my career and given me chance to co-learn with my students. It also keeps me updated with research topics.” She particularly enjoyed teaching at Berkeley last spring, where she and the class explored the mergence of migration and imagination by creating an installation of carry-ons, each displaying a variety of contents associated with these themes. “The students were energetic, proactive, and sensible. It was an amazing time.”

In September, she will begin teaching a master’s course in adaptive re-use at École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris. “I really want to use this time to think about what I have done in my career and to develop projects that change perceptions and realities,” she says.

She also hopes to find time this year to reflect, devote herself to drawing and reading, and focus on aspects of her work that usually end up on the backburner. “I am ready to focus on things I want to do, which is to continue experimenting and creating ideas. It’s a very exciting time.”

Given her track record, the outcomes are sure to be remarkable.