In our interview series ‘Her Story,’ we delve into the intriguing narratives of women architects around the world and shine a spotlight on the nominees of the divia award 2023.

Nzinga B. Mboup

“I want to be of service to people”:

DIVIA Award 2023 nominee Nzinga B. Mboup on the urgency to design equitable spaces and the need to question the true meaning of modernity

Nzinga B. Mboup, Senegalese architect and nominee for the divia award 2023, provides valuable insights into the advantages of multiculturalism, the impact of South Africa on the local approach within her practice Worofila, and her dedication to researching the urban and cultural heritage of Dakar

“The sensibilities that I’ve grown up with have always been fairly pan-African,” says Nzinga B. Mboup with a smile as she appears on my laptop screen in late September. Even though we’re on different continents—she in Dakar and I in Berlin—it doesn’t prevent us from delving deeply into her cultural roots. The architect’s career aspirations are closely tied to her upbringing, so it seems fitting to rewind and explore her background.

Nzinga B. Mboup was born in Mozambique to a Cameroonian mother and a Senegalese father. Growing up in the center of coastal Maputo, one of the most urbanized yet livable cities on the continent at the time, sparked her interest in African urbanities. The daughter of two diplomats, Nzinga moved around frequently as a child, becoming acquainted with various urban setups of places such as Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and the Central African Republic. Attending international schools, speaking multiple languages, and being exposed to a range of cultures, even within her home, has honed her sense of critical thinking and her self-perspective.

“It can be debilitating sometimes, especially when you’re living with these contradictions in a family environment, but it teaches you to have an open mind and to remain very critical while accepting differences on a profound level. It shapes you as a human being,” she explains.

“During my studies I always felt the sense of urgency to use the assignments to interrogate the context and to see how design could be used to make spaces a lot more equitable and of service to people.”

At 13 years old, Nzinga moved to South Africa, where she initiated her architectural journey. The idea was to choose a field in the built environment that would best contribute to systemic and holistic improvements across African cities.

“Growing up in South Africa was a very defining time in my life. It has also helped shape who I am as an architect today,” Nzinga reflects.

Before embarking on her studies at the University of Pretoria, she lived in South Africa for four years with her parents in what she describes as a somewhat isolated “diplomat bubble”. It was only at university that she started learning about the spatial history of South African cities.

“It was very disturbing because you still see [the inequity] in the way that the city operates and realize that many of the social and human issues are also there because of spatial design, urbanism, and architecture,” Nzinga explains.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, spanning from 1948 to 1994, cities and urban areas were deliberately designed and structured to enforce racial segregation to uphold white minority rule. The apartheid government implemented a series of laws and policies, such as The Group Areas Act of 1950, designating specific areas for different racial groups. Black South Africans were forcibly relocated from urban areas to segregated townships on the outskirts of cities. These townships were often overcrowded and lacked basic amenities. The government provided minimal resources for infrastructure, leading to poor living conditions.

“During my studies, I always felt the sense of urgency to use the assignments to interrogate the context and to see how design could be used to make spaces a lot more equitable and of service to people,” Nzinga says.

The opportunity to expand on this approach arose at 26’10 South Architects, an architectural practice in Johannesburg that was run by Thorsten Deckler and Anne Graupner (since 2020, Deckler has been running it alone). The name of the firm, signifying the latitude of Johannesburg, is meant to reflect their commitment to the city. Shortly before Nzinga’s graduation, one of her tutors suggested that the firm would be the perfect place to start her architectural career because of the studio’s mindful ideology. Mboup trusted her teacher’s instinct, applied for the position, and got the job straight away.

During her two years at the practice working as an architectural assistant, she contributed to the development of a live-work unit designed to house the office, as well as a taxi rank in the Diepsloot township in the north of Johannesburg. The studio was highly familiar with the context, having studied the neighborhood for years thanks to a research grant from the Goethe Institute. For an ambitious and value-driven architect like Nzinga, this was the perfect place to start.

“Many preconceived ideas are associated with working with earth and other biomaterials. Too many people may feel like it’s not durable and echoes a pre-colonial past associated with rurality and precarity. But, actually, some of the oldest buildings on this planet were built with earth.”

“It was the studio’s transdisciplinary approach to architecture that I found very enriching, and, just in general, the fact that the two principals had a very open and curious mind, liked to experiment and that they were very close to students and young people,” she explains.

It was also Nzinga’s former employer, Thorsten Deckler, who played a pivotal role in encouraging her to take a leap of faith a few years into her career and move to Senegal. At the time, she was living in London and working for Adjaye Associates as an architectural assistant when the unique opportunity to build her parents’ house in Dakar presented itself.

“He told me, ‘If you have the opportunity to do it, you really should because it’s only through that that you will become an architect. It doesn’t matter what the scale is: you need a project that you see through from beginning to end.’ For him it was a no-brainer.”

Six months later, following Deckler’s advice, Nzinga moved to Dakar, where her parents had recently relocated from South Africa. Under the guidance of two mentors, she started working on the design of the Keru Mbuubene, a house that also served as a case study for her ARB/RIBA Part 3 qualification at the University of Westminster, the final step in receiving her qualification as a registered architect in the UK. (Before moving to London, Nzinga completed a master’s degree in Architecture at the University of Westminster.)

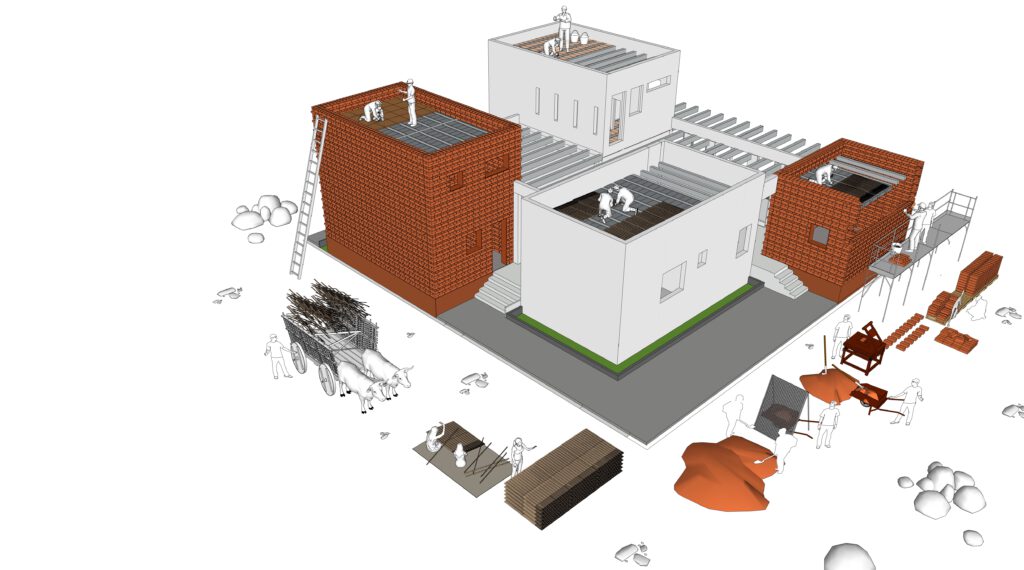

The house is a reconstitution of the traditional compound housing typology, where four individual units are organized around a common living area. For economic and sustainability reasons, Nzinga extracted two volumes from the existing unfinished L-shaped house built on concrete and added two more volumes in CSEB (compressed and stabilized earth bricks). She used shells for the floor finish and local timber for the windows and doors. After five years, the house is currently in the final stages of completion.

Local timber was used to build the windows and doors. © Worofila

Mboup’s original plan was to stay in Senegal for the project’s duration. However, little did she anticipate that this journey would later lead her to Worofila, her very own architectural practice in Dakar. Founded in 2017, it began as a collective of five architects and engineers united through a competition entry. These days, Nzinga co-leads it with her co-founder Nicolas Rondet. Named after the street in the historic Fann-Hock neighborhood where their office is situated (inspired by 26’10 Architects, it seems), Worofila is currently a team of eight professionals who prioritize the local community and pride themselves in their genuine commitment to teamwork: “Collaboration is at the core of everything we do. The real kind, not just the buzzword,” Nzinga says with a laugh.

Worofila primarily work with clay-rich raw earth and typha plants which, thanks to the alveolar composition of the fiber, serve as effective insulators. The firm believes in employing natural materials that align with Senegal’s weather conditions. Situated in the most western part of the African continent, Dakar experiences a hot and arid climate. The city sits on the peninsula known as Cap Verde, originally named for its lush greenery, however, the current reality paints a very different picture: “It’s very striking to go from the green cape to the sea of concrete,” remarks Nzinga. With concrete being the most accessible and inexpensive material, much construction has been initiated independently without proper supervision, resulting in subpar outcomes. The reality has led Mboup’s practice to focus on bioclimatic design and construction, which involves the use of earth but, unfortunately, doesn’t come without its challenges.

“Many preconceived ideas are associated with working with earth and other biomaterials,” Nzinga begins.

“If you say that you want to make a roof out of fibers, too many people may feel like it’s not durable and echoes a pre-colonial past associated with rurality and precarity. But, actually, some of the oldest buildings on this planet were built with earth, and there are also thermal benefits to using biomaterials,” she explains and names the impluvium houses of Senegalese Casamance area as an example.

“Everybody [in Senegal] aspires to a modernity, but the problem is that it’s a kind of modernity that we haven’t really questioned. Why did we ever stop building with earth? It’s something that has been conveyed, also politically, because cement and concrete offer many advantages for establishing an industry. But there’s obviously a counterexample that hasn’t been brought forward. And what we at Worofila try to do is ensure that it can come forward to a form of contemporaneity.”

Worofila’s past and current projects include public facilities, as well as single-family houses of different typologies, situated both in Dakar and outside of the city. This includes the NKD house (2021), a four-story family home in Dakar that optimizes space on a tight 150sqm plot. The house is designed around two atria that bring in natural light and allow for cross-ventilation in almost all rooms. The ceilings and floors are constructed using self-supporting vaults made with small earthen bricks and isolated from sound and insolation with typha blocks. The façade design, similar to previous projects, alternates two courses of bricks with one protruding thus casting shadow over the walls, which in turns reduces the amount of sun and heat absorbed by the external walls.

“Everybody [in Senegal] aspires to a modernity, but the problem is that it’s a kind of modernity that we haven’t really questioned.”

It is designed around two atria that bring in natural light and allow for cross-ventilation in almost all rooms. © Worofila

One of Worofila’s most significant projects, arguably, is the regional train line that connects the capital to the new Dakar-AIBD airport. This project includes the renovation of some stations and the construction of new ones. For the smaller ones out of 14 stops, Worofila has collaborated with GA2d, another Senegalese architectural practice, to create a robust architectural foundation using stabilized earth bricks. The design also features a canopy roof with an autonomous structure that facilitates air circulation.

The main project, scheduled to commence construction next year, is the Sebikotane station, a passive building constructed with earth. Additional initiatives include a masterplan for the people who were displaced due to the construction of the train line and the development of social amenities in close proximity to the areas traversed by the rail lines.

Worofila’s repertoire also counts her collaborations with the French Institute and the Goethe Institute in Dakar. The former involves the renovation and extension of the courtyard and art gallery. The latter is a collaboration with Pritzker Prize winner and Berlin-based architect Francis Kéré on the Dakar location of the cultural institute.

“Working with Kéré Architecture has been a privilege,” says Nzinga. “As local architects, Worofila helped assist the project through the permitting process and overseeing construction. We’ve also paid particular attention to facilitating the implementation of the earthen walls,” she concludes.

As a still fairly new practice, Worofila is thriving, keeping the team busy with different assignments, but Mboup’s unwavering commitment to Dakar’s architectural development extends beyond her practical pursuits—something that does not go unnoticed in the industry.

“What I find particularly appealing about Nzinga’s work is her commitment not only to sourcing local material but her continued research into Dakar’s urban and cultural heritage,” writes Mariam Kamara, a distinguished Nigerien architect and founding principal of atelier masōmī in an email.

As DIVIA’s Advisory Board member, she nominated Nzinga B. Mboup for the inaugural international DIVIA Award 2023 that celebrates extraordinary women in architecture. (The feeling of admiration is mutual: “To be nominated by Mariam Kamara, a fellow West African female architect doing work that centers the questions of sustainability and interested in creating a distinctively African language in architecture, is a true honor.”)

In addition to leading a practice, Nzinga co-authored the exhibition DAKARMORPHOSE, a collaborative effort with her friend and architect Carole Diop, on the evolution of the Lébou villages and urban and cultural heritage of the city.

“We wanted to do something for the Dakar Art Biennale because it’s such a massive cultural and arts event for the continent, but it didn’t include anything about architecture,” Nzinga begins.

“We started investigating this idea of identity and metamorphosis in the city, and it was pointed out to me by Carole that there were some places in the city center that still retained traces of indigenous urbanism. I didn’t believe it at first, because central Dakar is densely urbanized with high-story buildings everywhere. To go there and to realize that there are some places that still have trees in the middle of courtyards and have been more or less untouched all these years really intrigued me,” she concludes.

“I am overall so glad that I get to know many of my contemporaries and that we are creating a network of solidarity, collaboration, and care.”

Throughout their research, which concentrated on the endangered heritage of the Lébou culture and its territorial dynamics, the duo delved into the city’s original construction, exploring how Indigenous communities preserved a genuine social and political organization despite the city’s expansion. Their findings culminated in the exhibition DAKARMORPHOSE, showcased at both the 2018 and 2022 Dakar Art Biennale. Currently, Nzinga and Carole are engaged in a collaboration with Raw Material Company for an exhibition that reflects on the architectural and urban heritage of Dakar.

Additionally, Mboup is a lead on Habiter Dakar, a research project initiated in 2019 in collaboration with Caroline Geffriaud and the Goethe-Institut Dakar. It centers on the evolution and challenges of housing in the Senegalese capital and is intended to be published in a book soon.

“In Habiter Dakar, we were able to really push the reflection further than we already do at Worofila, which is to look at the shell and the material processes of how the building can provide physiological comfort. We also question the usage of spaces in general, depending on the type of rituals performed there,” she explains.

Nzinga’s efforts have proven to be fruitful beyond the Senegalese borders. Recently, she was appointed as a Curator by the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal for a three-year research project. The idea is to examine the architectural traditions of Senegal, particularly emphasizing the work of the first generation of Senegalese architects. The research aims to understand the materials and construction techniques that have played a role throughout the country’s history.

“I’m particularly excited about all the research projects, because it means that we can investigate research through the lens of the practice: climate design, materials, but also sharing the knowledge that we gain,” says Nzinga.

From her early experiences navigating diverse cultural landscapes to the innovative projects undertaken by Worofila, Mboup’s architectural pursuits reflect not only a dedication to sustainable, bio-climatic design but also a profound understanding of the social, cultural, and historical contexts that shape our built environments. As she embraces roles in research and education, collaborating with institutions globally, Nzinga remains at the forefront of envisioning a future where architecture serves as a catalyst for positive change. With all the exciting endeavors she has recently embarked on, all of them seem to be connected to improving her practice, serving others and enhancing collaboration with her peers.

“When I started my architectural journey as a student, I had very little to none references of African female architects doing critical work outside of Danielle Diwouta-Kotto in Cameroun and Djouga Diouf in Senegal,” Nzinga remembers.

“I am overall so glad that I get to know many of my contemporaries and that we are creating a network of solidarity, collaboration, and care.”

Text: Veronika Lukashevich