Maryam Pousti

“We’re going to lack many professionals in our country in the next years, it’s a tragedy”: architect Maryam Pousti on the political and architectural climate in Iran

It’s been precisely a year since unrest erupted across Iran following the death in custody of 22-year-old Jina Mahsa Amini. She had been arrested by morality police for allegedly violating the rules requiring women to cover their hair with a hijab. Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, women have been obligated to wear a headscarf covering their hair and neck in public. Any violations of this rule have been met with severe violence. Over the past 12 months, Iranians have taken to the streets in more than 160 cities to protest against the government and advocate for women’s rights. Thousands of individuals have been arrested, with many of them subjected to torture and even facing the death penalty. To say that the atmosphere in the country has been tense would be an understatement.

“I couldn’t sleep for two days,” says Iranian architect Maryam Pousti as she recalls the first days of unrest in Tehran.

“I saw it with my own eyes, how the police were hitting people, girls in particular. It was very scary, so I didn’t even dare to go out there twice.”

As we speak on August 23 via Skype—something that wouldn’t have been possible just a few months ago when the government shut down the internet to silence protesters—it’s been two days since the commission approved a new law, imposing stricter measures regarding Islamic dress rules.

Maryam Pousti is convinced that despite some unfortunate incidents, the overall impact of the new law will be ineffective. “It’s going to fail,” she says firmly. “So many people are not obeying the government anymore. And the more people disobey, the harder it is for them to control us. I just attended a university lecture and not one woman was wearing a headscarf.” Neither was Maryam Pousti.

“I am going to tell you something really simple,” she continues. “I don’t wear the headscarf in my car. I try to be careful, but I’ve already received multiple fines requesting me to face the authorities. No one will do this voluntarily, but because the fines have been accumulating, the government hasn’t been able to follow up. And what are they going to do?” she says matter-of-factly. “Shut down the whole country? It’s these little steps that you have to take to fight against it.”

The United Nations (UN) and the organization Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRA), however, say that there is indeed cause for worry. On September 1st, 2023, the UN issued a press release stating that their experts expressed “grave concern” over the new law that amounts to “gender apartheid”. The law, that could jail women for ten years for not wearing a hijab, now awaits the vote by the Iran’s Guardian Council; the bill is likely to come into force as early as October 2023.

Despite an initial collective state of shock, the people (“both genders”, as Maryam Pousti specifies) do feel engaged to speak up. “Women have been suppressed so much since the revolution that the more these kinds of laws are imposed, the more people are reacting to them. The young people in particular are really fed up with the situation. They have no future here, so in a way, they have nothing to lose.”

The prospects are indeed bleak. Amidst a deep economic crisis that began in 2017 and following last year’s nationwide protests, Iran has experienced a notable increase in emigration. While there are no exact figures available on the number of people leaving the country (emigration statistics are considered a matter of national security), Dr. Saeid Moidfar, chairman of the Iranian Sociological Association, points out that many have reached a breaking point. He shared these sentiments with Iran International in February of last year: “You reach the point where you think this is no longer a good place to live, and you should leave as soon as you can when you feel you are in a country where you are not involved in the decision making system, the country is not being run based on sound principles, your overall economic misery is increasing by the day, and social values are being sullied.”

More and more industries, including healthcare, IT, and engineering, are losing staff. Architecture is no exception, as young graduates and professionals are moving abroad in hopes of starting anew outside of Iranian borders.

“This is one of the problems that I’m facing in my studio,” says Maryam Pousti. “And I know a lot of my colleagues who are more experienced than me and who have had their offices for a longer time, even they are having this issue that they cannot get the younger generation to come and work for them. We’re going to lack so many professionals in our country in the next years. I can already see it. It’s a tragedy.”

Maryam Pousti has been leading her eponymous studio in Tehran since 2013 after earning an architectural degree at the prestigious Architecture Association in London. The way her home country tends to treat women had certainly been a factor in her decision to study abroad.

“There is a gap for sure. You might have university teachers who are fantastic, but then you have to be in an environment that is really downgrading. I didn’t want that,” she explains.

In an institution like the AA, with numerous household names in architecture serving as professors, there was certainly no shortage of mentors and guidance. For example, Pousti was taught by Peter Salter whom she credits as her biggest influence. “With every decision I make, I am recalling what he has taught us,” she says. “It’s all about the context. Why should this be here, why should it look like this? Why this form, why this design? It’s always at the back of my mind.”

After her first professional experiences working for Zaha Hadid Architects and Foster + Partners in London, Pousti decided to return to her home city Tehran in 2011 to try and make a name for herself. The reason is personal: she was craving the ability to work on her own terms at a place that is meaningful to her and where she is not forced to execute anyone else’s vision but her own. Naturally, I ask her about her initial reservations regarding working in Iran as a woman in a leading position – did she face challenges in being taken seriously?

“Things are changing so rapidly in Iran,” she says. “Maybe if you asked me this four or five years ago, I would have said, yes, it’s difficult. But I also think that the protests have opened people’s eyes to the fact that look, all these people fighting and facing the guards are girls. So, now when I go to a meeting, I feel like men respect women more,” she says, clearly referring to the developments on the societal level.

“People used to live in single family houses with gardens but because Tehran grew so much, all these houses have been torn down and built into apartment blocks.”

While Maryam Pousti is still in the process of defining her architectural mission, it is evident that her passion for architecture has its origins in Iranian history. Regular family trips to Isfahan, a historic city in central Iran that boasts a variety of architectural styles, including Islamic, Christian, and Persian, have left her mesmerized by its decadence since she was very young.

“Every time I went there, I was just like: I don’t want to leave this city,” she remembers. “The architecture, the proportions, and the way the light moves in these buildings is amazing. It has the most beautiful bazaar, which is in the main square city. I was always intrigued by that. As I got older, I started to appreciate it more and more. And I don’t know, maybe it’s just seeing that, being in that space that made me think of architecture [as a career path].”

Tehran, on the other hand, has undergone extreme architectural transformation over the years. In just four decades, it turned from a city with infinite gardens and single-family dwellings to a city of infinite apartment blocks. The lifestyle shift has influenced the quality of living, as most schemes are executed by developers aiming for an easy, convenient, and inexpensive construction, which often results in compromising spatial quality.

“Downsizing is the main issue, since this is something that we as Iranians are not used to,” Pousti explains. “People used to live in single family houses with gardens but because the city grew so much, all these houses have been torn down and built into apartment blocks.”

Architecture in Iran is becoming more adaptive, she says, and the materials are shifting towards more economical ones.

“Looking back, I could easily argue that the quality of the finish, the attention to detail, the materials in certain areas of Iran were much higher than something that was being done in central London,” she continues. “Now, of course, that’s changing—which is not necessarily a bad thing,” she adds optimistically. “You just have to be more creative about it.”

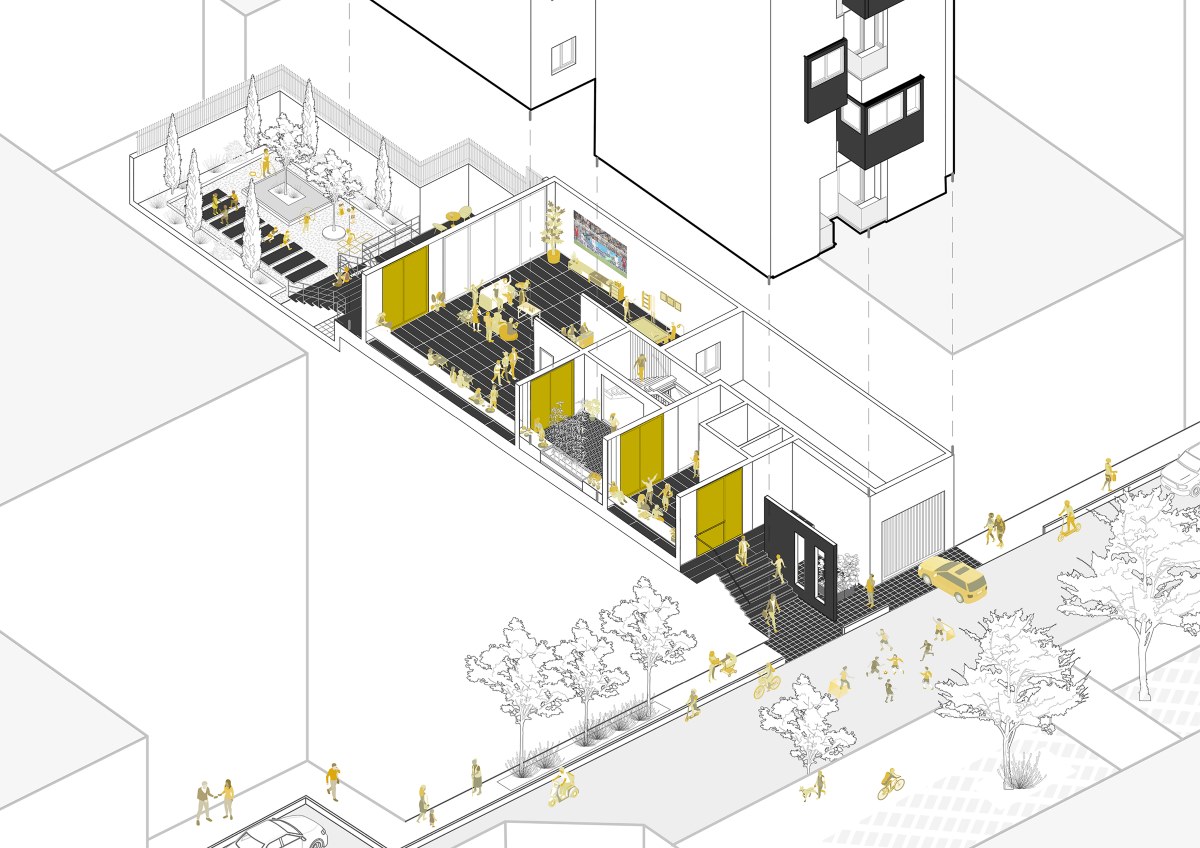

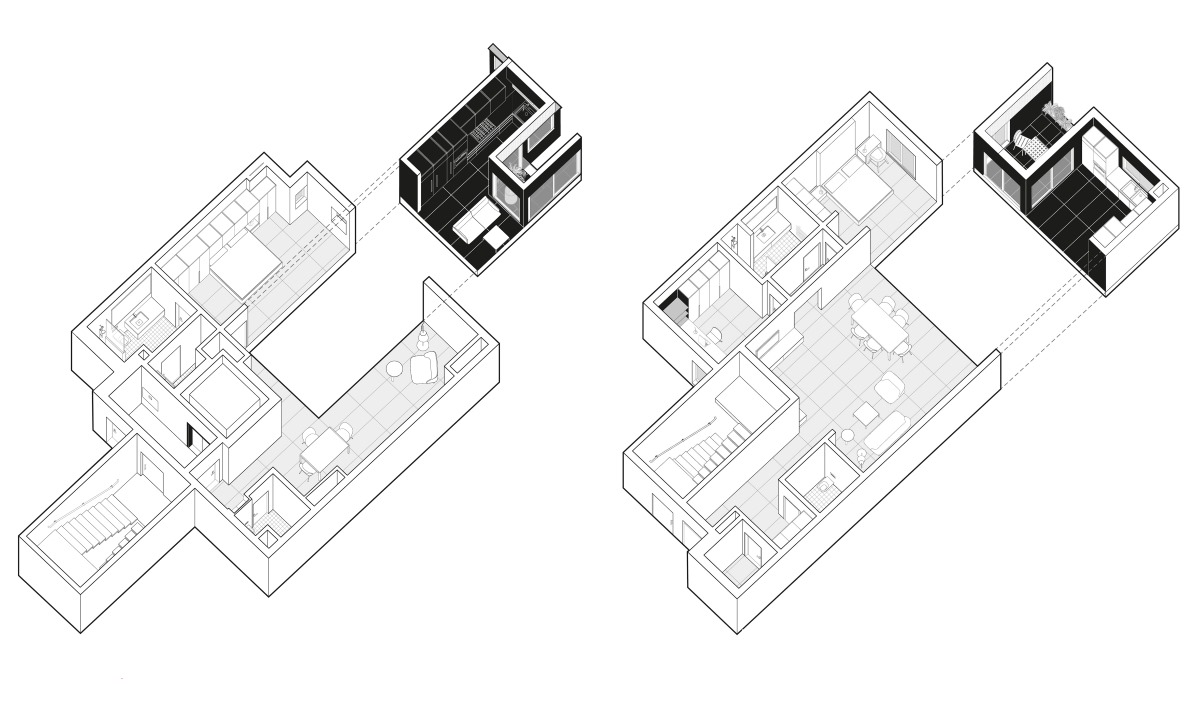

In her work, Pousti is trying to offer exactly that—a creative alternative to conventional models of habitation and dense urban living. This effort is most evident in her residential scheme VOID+ (2021), the first ever project that she has done entirely on her own and which was exhibited at Biennale 2023 as part of the “Time Space Existence Exhibition” at Palazzo Mora. Here, she is trying to regain the relationship between buildings and their urban fabric. To put it simply: the idea is to create a dialogue between the building, the street, and the neighbors.

The building is located in Northern Tehran on an extremely narrow site. It consists of two units of about 80 square meters on each of the 5 floors. Each unit sits around an intimate balcony, which is perceived as an interior garden. The rectangular stairwell acts as a buffer to prevent sound and direct visual contact between the units.

The distinct feature is a void, strategically carved into the north façade in an attempt to engage the building with its periphery and bring in the light.

To architecturally foster a connection between the community and the place, Maryam Pousti created a lobby that is stretched 20 meters along the length of the building, all the way from the entrance to the back garden.

“In an apartment building you can usually never see the depth, so we are trying to change that here,” she explains.

In her work she also strives to celebrate the value of working with artisans. This is evident in the combed horizontal cement pattern of the façade, which also acts as a conductor of rainwater, keeping the building clean. Door handles, railings, lighting fixtures and cabinets have been skillfully integrated in the architectural detailing of the building. In this project, working together with artisans of different backgrounds is meant to serve as a reminder that buildings are the result of substantial dedication and time.

Maryam Pousti’s main focus is to create quality in the spaces. For this residential scheme, she conducted extensive research, analyzed the neighbors and street dynamics—yet not without facing some criticism along the way.

“The neighbors were not happy about the design at first,” she admits. “A lot of them were skeptical because it did not look like the other buildings. But many truly changed their minds once the building was finished, because they saw how inviting and unconventional it was.”

What gave her the confidence to see it through?

“It’s a good question. I think I just went with it, took a risk. And the more I went with it and the building took shape, the more people recognized that it was working. I didn’t know what effect it would have; architecture is always filled with so many surprises.”

“Here in Iran, it’s such an extreme context, which is interesting at some levels and very disturbing at others. We don’t know what happens tomorrow. These are limitations that you need to work with as an architect.”

Maryam Pousti certainly has her share of projects she would like to pursue in the future, though the current socio-political climate in Iran has her dreaming more realistically. She is about to design what is supposed to become a private office in Tehran. The future is uncertain, so she prefers to keep the scales a bit smaller. “A lot of projects are on hold and may not be happening anymore—and if they do, the budget is so different from what we had anticipated two years ago, so you really have to adjust,” she explains. “If before people used to ask themselves, ‘how can we do this the most exciting way?’, now they think about ‘how do we do this the economic way?’ But you know, I’m just so glad that I have the jobs and the projects that pay my bills, so I am going to focus on that and then we can think about everything else.”

Certain future architectural needs, however, can already be anticipated. This includes the necessity to address housing for the older generation that culturally is used to living with or close to their children.

“Since people are leaving the country and having no or less children, there is absolutely no infrastructure for the older generation,” Pousti explains. “The government doesn’t think about it, and the private sector in Iran hasn’t been interested in investing in this sector.”

With such grim prospects, I do wonder if she ever thinks about packing up her bags and leaving— this time for good. Her urge to stay, as I learn, goes beyond individual ambition; it is rooted in deep curiosity and connection.

“It’s hard, but at the same time, it’s extremely exciting to be here because you have these two forces fighting, you know?” she tells me. “Either you stay where you belong and where you have your roots, or you go somewhere that affects you in some way. Here in Iran, it’s such an extreme context, which is interesting at some levels and very disturbing at others. We don’t know what happens tomorrow. These are limitations that you need to work with as an architect,” she says then pauses only to conclude with a highly relevant thought:

“Iran is one of the most interesting places to be if you want to make a great difference. Now I’m thinking, with all these traumas that Iranians have experienced, how do you design a space for them, for their children?”

I look at her expectantly, but this is a question she is yet unable to answer.

“It’s too early to say,” she concludes. “Only time will tell.”

by Veronika Lukashevich

Photography by Persia Photography Center