Manuelle Gautrand

“I want to feel the intimacy of our projects”: French architect Manuelle Gautrand on the importance of emotion and communal spaces in architecture

The winner of the European Prize for Architecture, Manuelle Gautrand, speaks about poetic architecture, her pioneering use of rammed earth at a grand scale in France, and how her projects Edison Lite and Alma Terra, currently exhibited in Venice until November 26th, introduce a new model of housing

Ever since she was a little girl, Manuelle Gautrand has been in love with cities. Born and raised in Marseille in southern France as the daughter of architect parents, she developed a keen eye for both the science behind and the emotional resonance of urban spaces. Observant from an early age, she paid close attention to the Mediterranean light, its brightness and dark shadows.

“The quality and ‘density’ of the light are very important for me,” she says in our Skype interview in early October. “In Marseille, the climate is not very smooth, so the light is full of contrasts. When I recently traveled to Sweden, I discovered how much the light is different there, how pale it is and lacks any density.”

Manuelle’s fascination with light is intertwined with her admiration for art, specifically for the late French painter Pierre Soulages, who died in 2022. Studying his work, which is known for his groundbreaking use of black paint, she discovered the richness of the black color and how it varies once the sun’s rays touch a surface.

“I try to see art in a deep way,” the architect explains. “I want to understand the root and the condition in which it has been made to be closer to the artist.”

Certainly, this mindset is reflective of Gautrand’s architectural methodology: embracing diverse influences while delving into the essence of a location, she aims to truly honor its intrinsic character.

In addition to her love for art, she draws inspiration from nature, likely influenced by her late father, an urbanist she affectionately calls “the protector of the environment”. Even so, exploring new cities is unquestionably her favorite way to travel.

“The city is my native place,” Gautrand says smiling. “It’s a place that I continuously try to analyze.”

When on a trip, she takes mental notes of the (often ancient) urban architecture she encounters, considering as many contextual elements as possible. Selecting a single standout town is an impossible feat, and if she did, as Gautrand humorously remarks, “it would be a very long interview”.

But there is, indeed, a place that had a lasting impression on her during the early stages of her career. At the age of 20, shortly after entering into her studies, Manuelle Gautrand visited the Opera House in Sydney—a moment she still vividly remembers.

“I was totally shocked,” she reflects, recalling her first encounter with the building.

“By the architecture but also by the scale of the bay and the landscapes in Australia. Suddenly, I discovered something else than the European. The opera was both monumentally powerful but also contextual because it was precisely sized to fit the scale of the bay. So, the building was both monumental and poetic in a way.”

The Opera House was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on October 20th, 1973, and has since been considered as one of the greatest works of architecture, attracting over 10 million visitors per year. This October it celebrated its 50th birthday with free tours and a light show illuminating the building.

“It’s important for the people to have leisure in our buildings, to feel emotions and the intimacy of our projects, to be impressed. We need to consider the emotional dimension.”

Manuelle Gautrand probably didn’t know it at the time, but “poetic” would later become a fundamental description of her practice’s philosophy.

“To me, the poetic dimension of architecture serves as a means to evoke emotions,” she explains.

After completing her architecture studies in Montpellier and working for six years in different French studios, Manuelle Gautrand opened her eponymous firm in 1991, first in Lyon and later, in 1994, in Paris. Since then, she’s worked on a variety of projects, including leisure and sports facilities, theaters, museums, and cultural centers.

One of her early notable endeavors that captured widespread attention was the Citroën’s flagship showroom when it opened on Paris’ Champs-Elysees in 2007. This showroom, accessible to the public, boasts a striking six-story glass atrium. Inside, there is a vertical arrangement of eight Citroën vehicles, visible to visitors as they walk up the spiraling staircase. Some years later she converted and refurbished the Gaité-Lyrique Theater into an interactive center for modern music and digital arts, both open to artists and public visits. From 2003 to 2010, her firm renovated and extended the Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art in a park in Villeneuve d’Ascq, aiming to seamlessly integrate new galleries while respecting Roland Simounet’s original architecture.

“I tried to take my cue from Roland Simounet’s architecture, ‘to learn to understand’, so as to be able to develop a project that does not mark aloofness, an attitude that might have been seen as indifference,” Gautrand writes in her description of the project.

In 2017, and 26 years into her career, Manuelle Gautrand’s thoughtful, bold, and non-conformist methods earned her the esteemed European Prize for Architecture. This achievement made her the first woman and first French architect to receive the prestigious accolade. This was a big deal for Gautrand, especially because the predetermined criteria for winning the prize are deeply ingrained in her philosophy: “the humanism, the poetic approach, the sensitivity and contextuality—these were the comments made by the jury I really appreciated,” she explains.

Since its inception in 2010, The European Prize for Architecture is annually granted by The European Centre for Architecture Art Design and Urban Studies and The Chicago Athenaeum. This renowned award is bestowed upon architects who have dedicated themselves to promoting the values of European humanism and the art of architecture.

It is indeed Gautrand’s inventive nature and determination that have catapulted her to the stratosphere of the architectural world, yet at the same time she consciously tries to ensure that ambition does not compromise the needs of the ones she designs for. Her aim is to always welcome people with sensitivity and to create a place of physical and emotional comfort.

“It’s important for the people to have leisure in our buildings, to feel emotions and the intimacy of our projects, to be impressed. We need to consider the emotional dimension,” she explains.

One of the newer projects to underscore this mission is Edison Lite (2020), a co-housing complex in Paris, designed to awaken the communal spirit among residents. Building a development in a small area of only a few hundred square meters posed a challenge.

“I was a little bit anxious because the site was already very dense, and my immediate concern was to work in a delicate way to minimize and even mask the density of this new addition,” Gautrand says.

“The idea of enveloping the project with plants was part of this goal: masking our building as much as possible, creating a filter to embellish the whole site and give to the neighbors a piece of nature to look at.”

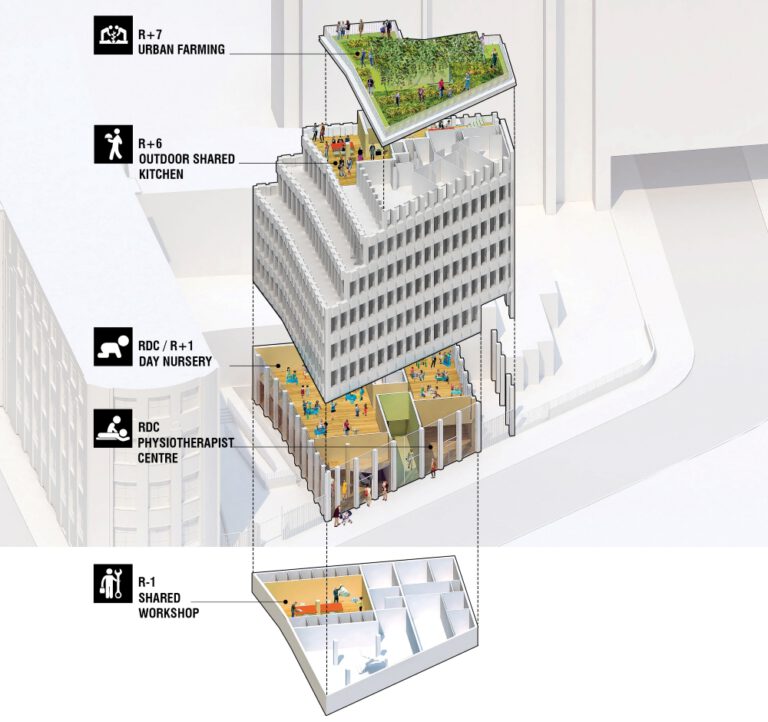

One of the winners of the “Réinventer Paris” competition’s call for innovative urban projects, Edison Lite introduces a new communal approach to housing without compromising the privacy of individual homes. One exceptional aspect of the project is that approximately 20% of the areas are dedicated to common facilities with specific functions, including a workshop on level 1 and an outdoor kitchen on level 6. The residents, who occupy 25 flats, had the unique possibility to co-design the brief for their home (soon realizing the complexity of the task) and moved into already fully landscaped units.

“I wanted the residents to arrive in a place that was already beautiful,” explains Gautrand.

Designed following the principles of edible permaculture, each tenant is allocated their own section of land in the roof garden. This 150m2 allotment enables them to cultivate their own food while enjoying panoramic 360-degree views. Additionally, a total of 290 windows were adorned with the same number of planters that had been planted during the construction over a year and a half prior. They have also been equipped with a basic automatic watering system. After moving in, the residents are expected to take over the responsibility of caring for the plants—a required collective effort to maintain the harmony of the place.

“I feel the need to be in a community, so as architects, we need to create architecture that welcomes it.”

It’s important for Manuelle Gautrand to highlight that these additional features are situated in privileged locations within the building, typically reserved for the most luxurious and costly apartments on the higher floors. The architect deliberately decided to allocate these exceptional spaces—offering the best views and ample sunlight—to be shared by all residents.

“The question for us is how to advance new ways of living,” she explains.

“I feel the need to be in a community, so as architects, we need to create architecture that welcomes it.”

“My architecture is always executed with a sense of the context of the history, the culture, the site, and the ecological impact,” she adds. “It’s a question of being inventive and doing architecture that is ecological.”

If there is a project in Gautrand’s repertoire that heavily relies on a sustainable approach, it would be Alma Terra in Montpellier that she started about six months ago. Launched by the City of Montpellier with the goal of creating a series of “follies”, this is the third building following Arbre Blanc (designed by Sou Fujimoto Architects, Nicolas Laisné Associés und OXO Architectes) and the Folie Divine (designed by Farshid Moussavi Architecture). Echoing the design of the first two, the development consists of five towers, varying in height between 8 and 11 levels. Every volume features about 30 dwellings, aiming to cultivate small communities.

“Alma Terra in Montpellier is a manifesto on the Mediterranean way of living,” says Gautrand who, having studied in the city, feels a deep bond to it.

The circular form resembles that of a sculptor meticulously carving out space to integrate the terraces that offer privacy, as well as shelter from wind and sun. (Fun fact: Manuelle Gautrand’s sculpture teacher had a profound effect on her when she was a student.)

The project aims to incorporate multi-level landscaping, ample communal spaces, implement passive sustainable system and the most impressive of all: reuse the soil excavated on site.

“This is a very innovative project, because this is the first time that rammed earth will be used at this scale in France,” says Manuelle Gautrand.

The project utilizes 12,000 cubic meters of excavated earth from basement parking construction to create rammed earth walls for the buildings. What’s unique is that this technique will be extended to upper levels (11 and 12), requiring additional calculations related to wind and temperature. Moreover, the project seeks to develop a new local construction facility and stimulate the local economy by producing the rammed earth elements on site. The use of cast earth for the facades and ensuring thermal inertia would allow to adopt a passive project approach, which does not come without its challenges and strict regulations. However, team Gautrand is optimistic and “on [their] way to succeed,” reassures the architect.

At the ground level, the towers meet the site boundaries, forming a spacious open area between them envisioned as a new public park. This space features pathways connecting various green areas. On the upper levels, the buildings are connected by walkways in separate clusters. These clusters are linked by double-height communal spaces, which function as outdoor terraces.

Alma Terra and Edison Lite present innovative solutions to improving the quality of life in urban collective housing. These initiatives are included in Reconceptualizing Urban Housing, which is part of the sixth edition of Time Space Existence, a curated exhibition organized by the European Cultural Centre. This exhibition serves as a platform for selected women-led practices from across the globe, each offering unique perspectives on collective housing. It can be visited at Palazzo Mora in Venice until November 26th, 2023.

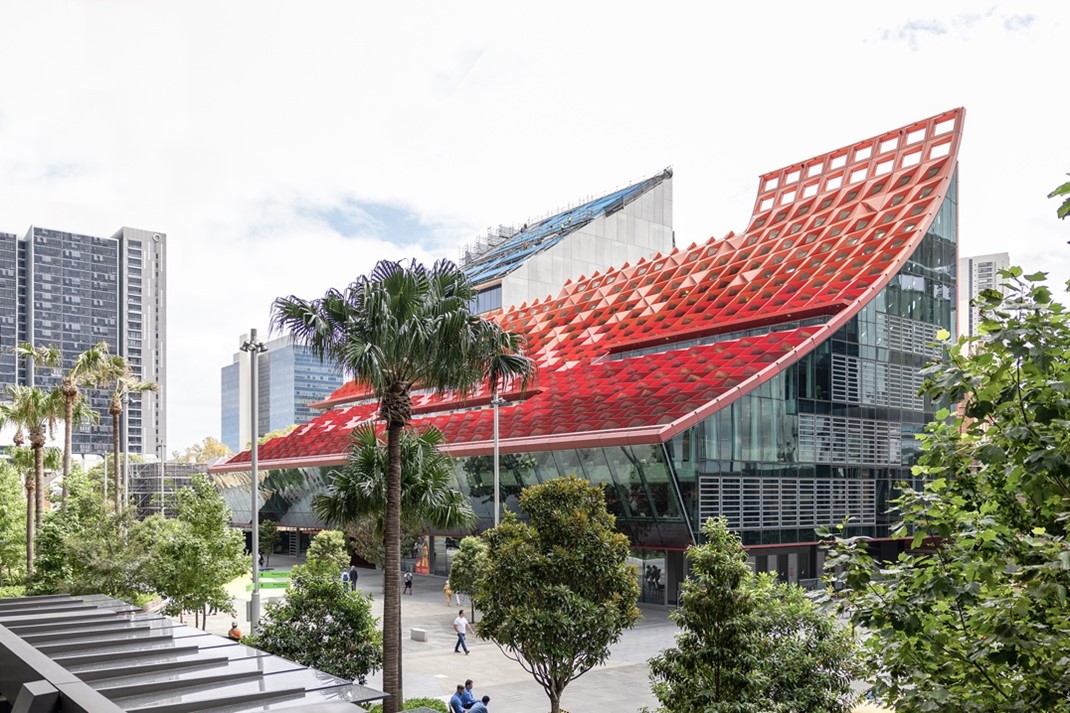

While Manuelle Gautrand primarily works in Europe, she recently completed a project down under: the smart PHIVE Community Center in Parramatta, which stands out for its sloped roof and promotes natural ventilation. It is meant to be a space to learn, be inspired and explore something new—an incentive clearly aligned with Gautrand’s own vision for herself and her firm. Since falling in love with the continent over 40 years ago, working in Australia must surely feel like a full-circle moment that would undoubtedly make her younger self proud.

But Manuelle Gautrand is just getting started. Always on the lookout for new challenges, she aims to explore uncharted territories and continuously expands the scope of her projects. In the coming month, she will begin work on a micro home situated in the heart of a forest—an architectural adventure she is not accustomed to but very enthusiastic about. While she refrains from sharing details at this stage, the process will most certainly look something like this: She will arrive at the site, rigorously analyze its history and context before starting the creative process with her team. Her studio employs around 20 people, as well as other independent and innovative companies from different disciplines, including landscapers, botanists, and engineers specialized in reused materials.

“It is very important to be patient, do the scientific analysis first and not let your initial ideas take over, because they are usually not very contextual,” she explains.

“As architects, we have the power to change the world and our living environment. So you need to learn how to listen. It’s a way of being receptive and modest.”

Text: Veronika Lukashevich