Gabriela Carrillo

on meaningful architecture and not willing to choose

For DIVIA’s first visit to Mexico City, Veronika Lukashevich met up with Gabriela Carrillo at her alma mater, UNAM University, where she has also been teaching. They spoke about Carrillo’s graduate research program, an architect’s job during a crisis, and encouraging students to follow their own paths.

On an early February morning, Gabriela Carrillo leads me into a small, empty room just outside the dean’s office at the Architecture Faculty of the renowned National Autonomous University (UNAM) of Mexico City. It’s the first day of a new semester, and we are meeting at 8 a.m., about an hour before her first class. The school is still deserted but it won’t be for long. With its open spaces and corridors, natural ventilation flows freely here, creating a breezy and comfortable atmosphere for effortless interaction among faculty and students. Settling into a cozy corner of the room, Carrillo quickly sends a text message to the group chat with her students, informing them that she might be running a bit late. “I looked at your questions and thought we need an additional 30 minutes,” she laughs.

Having studied at UNAM herself and taught here since 2003, Carrillo feels deeply connected to the institution, but like any long-lasting relationship, there have been some ups and downs. In 2017, she felt stuck and almost considered quitting. Balancing this role alongside leading her own studio, Taller Gabriela Carrillo, and being a new mother, she doubted whether she was truly adding value as a teacher. “I thought: ‘I don’t have enough time to review my own projects. I’m not sure I’m producing anything that makes sense for the students?”’, she reflects.

“There is no space for architecture in the middle of an emergency, but there’s space for planning and for understanding the problems in the city and country that we live in.”

That same year, on September 7th and 19th, two big earthquakes leveled Mexico City, claiming hundreds of lives. (The second one coincided with the anniversary of the devastating earthquake that shattered the capital back in 1985, adding another emotional element to an already catastrophic event.) In a collective effort to help rebuild the city, Carrillo joined forces with over 100 architects, including her current colleague at UNAM, architect Loreta Castro. Carrillo also involved her students in the process, teaching them first-hand how to handle a crisis. Together, they worked closely with a community in Tlayacapan, held seminars on vernacular construction at schools, and collaborated with a theater company to design a stage on the main plaza for cinema nights and performances.

“There is no space for architecture in the middle of an emergency, but there’s space for planning and for understanding the problems in the city and country that we live in,” she says. But trying to assist around 80 affected families took a toll on her and she soon recognized the constraints she was facing. “I failed as an architect,” she says devastated, thinking back to that time. “I quickly realized that we are not prepared enough for a city that has earthquakes.”

After a period of frustration, she rolled up her sleeves and adopted a solution-based approach. About a year after the second earthquake, she and Castro introduced a new Research and Degree Seminar at her University, Estudio RX. It focuses on Mexico’s social, economic, geological, ecological, and political vulnerabilities with the goal of raising awareness of the city’s shortcomings and inspiring long-lasting improvements in architecture and urban planning.

The initial three-year research program focused on fissures along the Santa Catarina volcanic line, affecting the Tlahuac and Iztapalapa municipalities, both heavily impacted by earth cracks. These issues stem from the city’s soft, compressible clay foundation, extensive groundwater extraction, seismic activity, and rapid urban development. The consequences are severe, leading to cracks in buildings, infrastructural and pipeline damage, and increased vulnerability to seismic events.

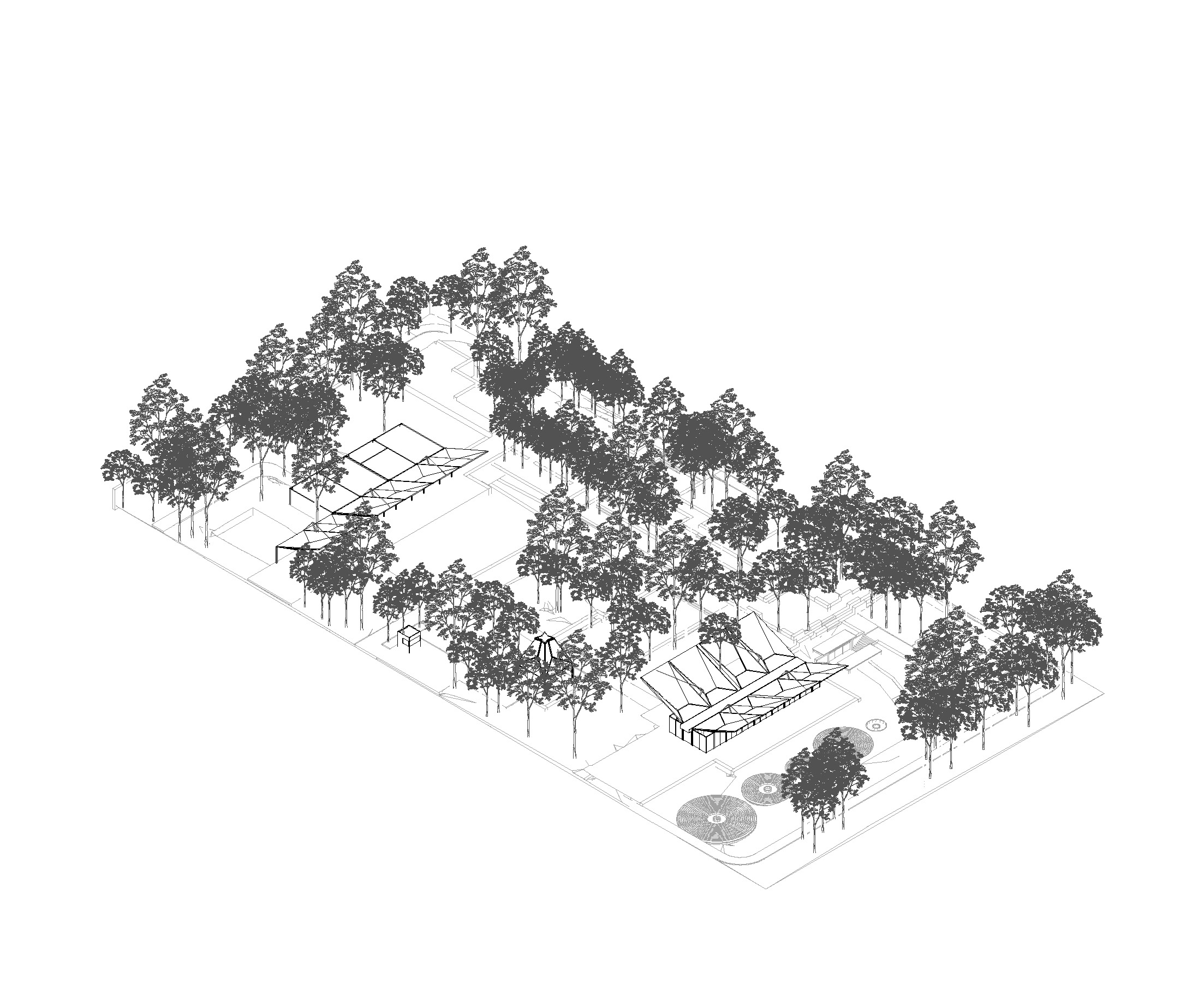

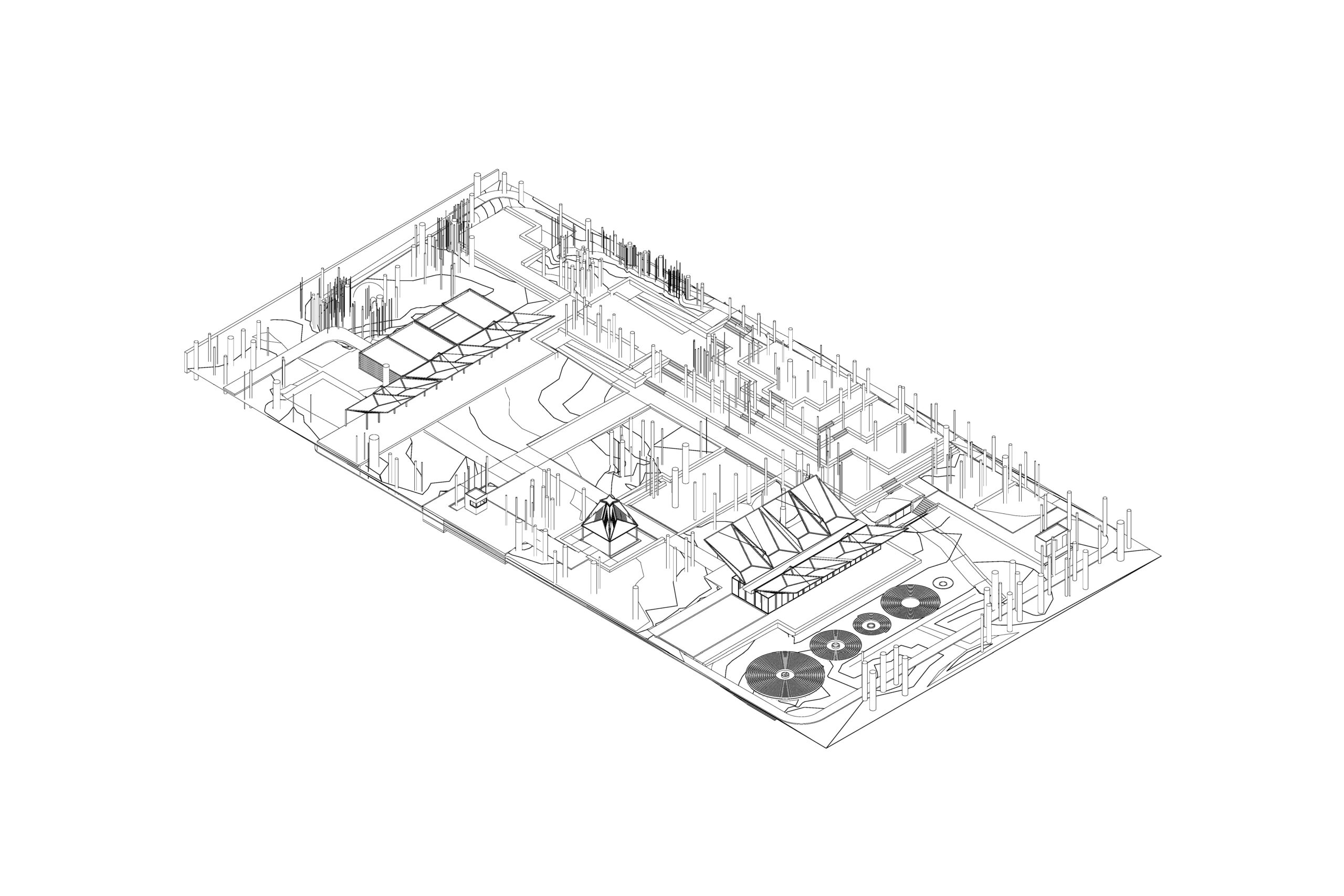

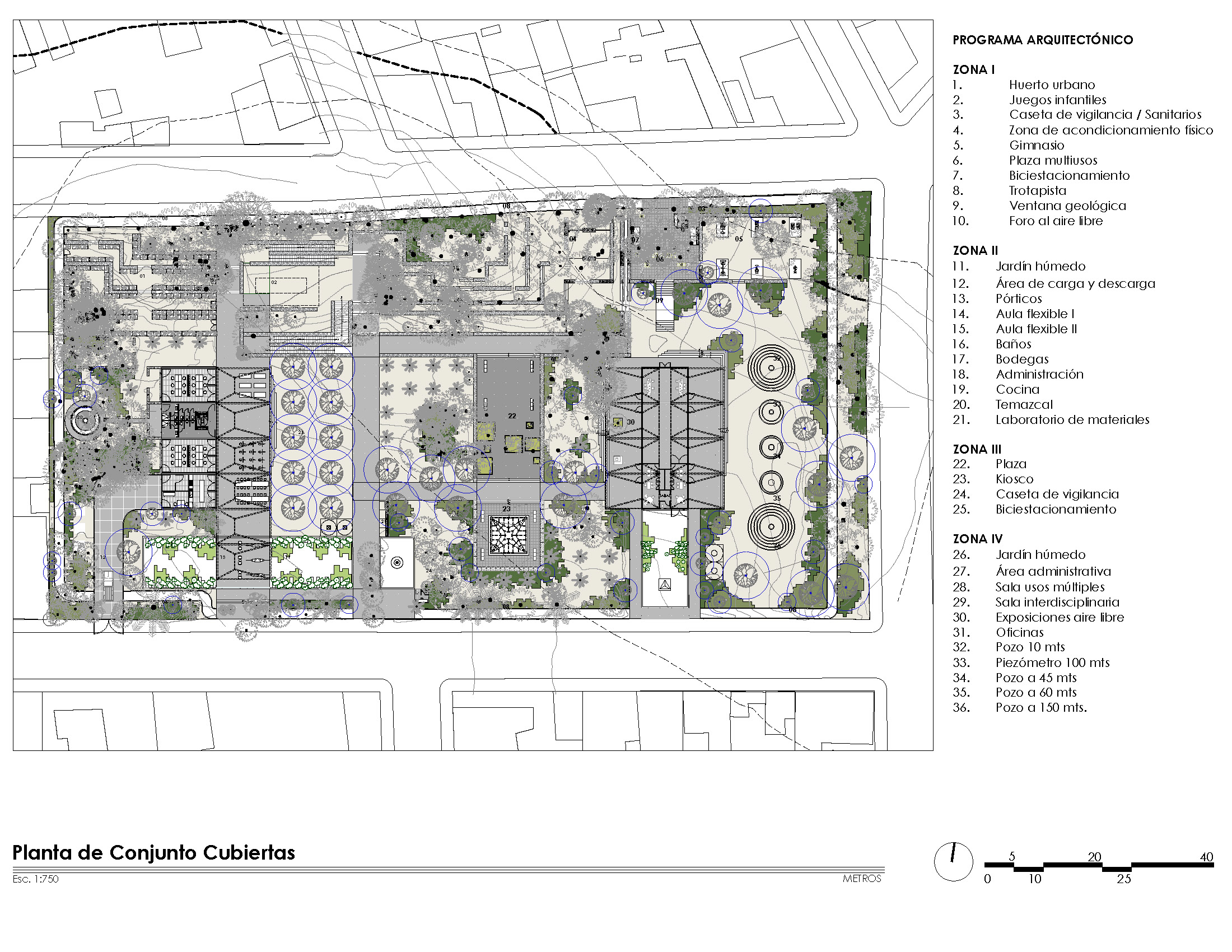

Under Carrillo’s supervision, graduates collaborated with the municipality to repurpose the site of a school demolished in the 2017 earthquakes, establishing a research lab and communal space. Dubbed “Tecoloxtitlan Utopia / Interactive Observatory of Subsidence and Fracture in Iztapalapa,” the project received invaluable input from a volcanologist, a geologist, and a geotechnologist, which, according to Carrillo, significantly enhanced its outcome. The Observatory encompasses both outdoor and indoor areas, featuring a kiosk, playground, and garden that double as a gathering place for the community, which lacks public spaces. Educational elements include a local museum and training studios where residents learn earthquake-resistant construction techniques for their homes and extensions.

“For [Loreta Castro and I], doing architecture has to do with being meaningful somehow,” says Carrillo. “It’s almost ridiculous to believe that we should just pay attention to creating art. And we love art! But we believe that we have inherited the idea of modernism and starchitects, and [this idea] kills the planet. I believe we have to break those paradigms and work collaboratively.”

As of 2024, Carrillo is concluding the third year of the second seminar cycle that focuses on migration in Tijuana, a Mexican border city south of California. The students enjoy complete freedom but are expected to deeply engage with every aspect of the process and the context they operate within. They are also required to stay updated with the news daily, which helps them develop a program centered on a problem they identified on-site. Among their initiatives is the establishment of secure areas with fire pits to provide warmth for migrants during cold and humid nights. “Migration is one of the most significant topics we face in the world today,” Carrillo says. “At the end you understand that you don’t need to build big buildings. [The result] needs to be impactful, so you have to understand the real requirements of the people you’re dealing with.”

Carrillo wants to empower her students to recognize the diverse avenues within architecture, encouraging them to forge their own paths without having to rely on traditional employment structures: “The university has 7,000 students, and only about 3% will be hired in a traditional way. That’s our Mexico,” she says with a shrug. “I believe it’s very important to make our students understand that they can produce their own projects as independent practitioners.” She makes an example: “Let’s say you know the weakest points of your neighborhood. You can develop a project addressing those problems and propose it to the municipality, for example. And if they decline, it doesn’t matter. You can produce your own work.”

“I believe we need to break the paradigm of starchitects and start to work collaboratively.”

Independency, tenacity, and curiosity have been ingrained in Gabriela Carrillo since her early years. Born in Mexico City to a mother who traveled the world as a flight attendant and a father who is a geologist, she developed an appreciation for the world’s diverse landscapes, vegetation, and topography from a young age. Carrillo views space as a complex, nuanced, and interconnected entity that is not confined to a physical structure. “Space starts here, in a dialogue, in the way we relate to each other, so it’s ridiculous to believe in building walls,” she says, drawing connection to Donald Trump’s infamous statements.

During her time at UNAM, Gabriela Carrillo was keen to dive into professional endeavors at the earliest opportunity. In her third semester, she won a university contest, earning her the chance to contribute to an actual government initiative. It was in 2001 that she commenced her collaboration with Mauricio Rocha, a partnership that culminated in the establishment of their architectural studio, TallerRochaCarrillo, in 2011. Fast forward to 2019, she took the bold step of launching her own studio, marking a significant milestone in her career journey.

During this formative time, Carrillo says she developed a “thinking process” that helped her connect with a space on a more profound level: paying close attention to the senses. She first explored this method in 2012 while designing the Library for Blind and Visually Impaired People in an existing building in Mexico City. She aimed to create a space that could be navigated through touch, sound, and spatial awareness, including features like tactile flooring, braille signage, audio guides, and flexible furniture. This project not only serves as a valuable resource for the visually impaired community but also stands as a testament to the power of thoughtful, human-centered design in enhancing the quality of life for all users.

Carrillo is particularly fascinated by sound in a room and how it can influence our perception of a place. She believes that silence fosters a deeply introspective existence, allowing us to tap into a more abstract aspect of ourselves. It’s intriguing to hear this, considering how outspoken she is in other aspects of her life and work, where silence has a negative connotation. For example, her advocacy for women’s rights, which stems from a personal tragedy—losing her cousin to domestic abuse, an experience that has profoundly fueled her dedication to standing up against violence against women.

“I pursue silence in my work because I believe that the quality of a space has to do with it. A place where you can feel comfortable to absorb yourself and free your mind in a way. But I also think it’s my responsibility to take advantage of my voice and to encourage young girls—or not only girls; in this diverse world, gender shouldn’t matter— to believe that they should have a voice. In that sense, yes, there are these two different ways in how I consider silence in my work.” Carrillo goes on to express that she’s grateful for organizations like DIVIA that encourage new voices. “I believe it is important to strengthen the voice of diversity that was kept silent. It used to be a monolog, not just from men, but from powerful men.”

This year marks a significant transition in Gabriela Carrillo’s career as she closes a major chapter. The Mexican architectural collective Colectivo C733, a collaboration with her husband Carlos Facio, Jose Amozurrutia, Erik Valdez, and Israel Espin, is coming to an end. Since its inception in 2019, C733 completed over 35 small public projects, including sports and education facilities, community centers, markets, and cultural buildings, many of these in vulnerable areas of Mexico. Some of the works among these include the Matamoros and Guadalupe markets, the Nacajuca Music House and Tapachula station, and the San Blas pier. Carrillo explains that the decision to close this chapter is partly due to the increasing amount of individual work for each practice. Additionally, political transitions might alter the policies that established the Program for Urban Improvements, within which C733 operated.

C733’s latest project is an eco-park in Bacalar in Quintana Room which is “the perfect example of what architecture means, at least for me, in the 21st century,” says Carrillo.

Sprawling over 7,000-square-meters, the park is framed by a dock of 200 meters per side. It provides access to Laguna de los 7 colores (lagoon of seven colors), one of the only spots in Mexico, which is home to the stromatolites, a living colony similar to coral. (The photos below were taken by Rafael Gamo.) The architects thoughtfully integrated the park into its surroundings, while providing visitors with solid spaces to learn about environmental preservation, including a museum showcasing a timeline of the area’s unique, 10,000 year-old history of the lagoon. The design also incorporated measures to control water runoff pollution from the village by collaborating with landscape designers and wetland experts. This was accomplished by implementing natural filters, creating depressions, and establishing rain gardens. For this, the team worked with local materials and light structures.

Carrillo admits that working on public projects is rewarding, but the pressure can be quite challenging. “It’s exhausting and [demands more] energy than private work,” she says. “I love to do public projects, but I need to balance them out.”

At this stage in her life, Carrillo is concerned with doing what feels right: as a mother, teacher, and practitioner. One way to maintain this balance is by focusing more on private commissions. While she remains skeptical about taking on projects that primarily benefit a select few, she’s reached a stage in her career where she prefers to work with people who have a similar understanding of the bigger picture. “I have excellent clients and I believe that you can achieve your best work when you are pursuing the same path,” she says. “These decisions are not easy because I live from what I do, but I believe it is important to be really honest when you are starting a professional relationship, even though you might lose a client because of that.”

Carrillo is also at a point in her life where she is trying not to make too many sacrifices, a reality that many working women face. “I don’t want to stop teaching, I don’t want to stop being a mother, I don’t want to stop going to the karate class of my kid, I want to take care of my plants, I want to read books that are not about architecture and not only start to read them and then fall asleep. I don’t want to choose! But to balance that is a big issue.”

While she might strive to take on as much as possible, Carrillo also recognizes that it takes a village to do it all. When overwhelmed with everything on her plate, she relies heavily on her circle of friends and family. “If you create a community, you can achieve a lot of stuff. As Latin Americans we have this sense of family which goes beyond—it’s the granddad, [but also] the nanny of my kid, it’s the community, the power of the house hold in a communal sense,” she says proudly. “We have that strength, so I want to keep taking advantage of that.”