Anna Heringer: “Beauty has nothing to do with money”

German architect, sustainability advocate, and UNESCO honorary professor Anna Heringer wears many hats, but they all align with a single vision: to show that architecture is a tool for improving lives. To mark the first anniversary of HER STORY, Veronika Lukashevich spoke to DIVIA’s co-founder about working with clay, and creating a building for female tailors and people with disabilities in Bangladesh

Environmentalism runs in Anna Heringer’s veins. “I have green blood,” she says with a smile, speaking to me over Skype from her office in Laufen, the Bavarian town on the Austria-Germany border where she also grew up. Raised in a household that was largely self-sufficient in food and clothing—her father is an ecologist—Heringer spent her summers as a Scout, living what she describes as a “fully unplugged life.” “We’d spend two weeks in remote places, building small settlements with materials we found in nature. It was amazing to see how much you can create on your own, even at twelve years old.” These experiences, where she learnt firsthand how versatile architecture can be, left her feeling empowered. “Architecture provides identity and protection, but it also fosters team spirit and community. That was a significant lesson for me.”

Today, with two decades of experience building primarily in Asia, Africa and Europe, an honorary UNESCO professorship in Sustainable Development, and an Order of Merit awarded by Germany’s president Frank-Walter Steinmeier in 2022, Heringer is one of the most respected architects in the world. Celebrated for her use of natural materials like clay and bamboo, she is committed to socially responsible design and honoring local communities. A self-proclaimed “stubborn idealist,” she continues to embody the values that were instilled in her during childhood, perfectly combined in her first major project—the METI (Modern Education and Training Institute) School in Rudrapur, Bangladesh.

Completed in 2006 as the culmination of her diploma thesis, METI earned Heringer international recognition when it won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007. During construction, everyone was allowed to help out. “I wanted to give my future users, the kids who were the same age as I was when I was with the Scouts, the chance to participate,” Heringer says. “You never just build a building; you also build up a community—if you do it the right way. That’s something that we have forgotten in our part of the world.”

“If we make our decisions out of love for others, society, and the planet, sustainability happens in a completely natural way.”

Heringer first traveled to northern Bangladesh at 19 years old to volunteer with the NGO Dipshikha, the same organization with which she would later build the METI School. Initially, she had hoped to go to Senegal or Côte d’Ivoire (“I was very much into African music and learning percussion”), but was offered a volunteering position in Bangladesh instead. At first, the change in plans left her skeptical: “We have so many prejudices when it comes to the Global South. My head said: ‘absolutely no,’ but my gut feeling said, ‘just go.’ Luckily, I followed my gut, and it was the best decision. Now, the moment I get off the plane there, I’m home.”

Already during her early days in Rudrapur, Heringer learned about the importance of using local resources after observing villagers crafting everything they needed for daily life by hand. “I quickly realized that beauty has nothing to do with money, but with awareness, care, and love,” she says. Hearing this, it’s not surprising then that she has updated the famous design principle “form follows function” to “form follows love” and integrated it in her practice. “If we make our decisions out of love for others, society, and the planet, sustainability happens in a completely natural way,” she explains.

(The hardcopy of Heringer’s eponymous book Form Follows Love that introduces the reader to her career and practice in the Global South and Global North will be published with Birkhäuser on 3 September 2024. The ebook is already available for purchase.)

Over the years, Heringer’s relationship with Dipshikha has only grown “stronger and stronger.” Their latest project is Anandaloy, a therapeutic center in Rudrapur designed for people with disabilities—a novel concept in Bangladesh, especially in rural areas where a high percentage of newborns with disabilities is often attributed to bad karma from past lives. This belief leads to concealment rather than inclusion of the affected in society. Poverty exacerbates this issue, as many adults are forced to work, leaving individuals with disabilities to fend for themselves during the day. “[Therapy centers are] not something people know about there,” Heringer explains.

But the mission of Anandaloy goes beyond providing therapeutic treatment. “It also offers opportunities for people with disabilities to learn, work, and engage with the community.” I feel compelled to share with her about a disabled member of my family and my perception that Europe—particularly mountainous Austria, where this relative lives—also lacks inclusive and interactive spaces designed specifically for those with special needs. She nods: “Architecture is often used as a tool to prove power or show off, but it also has this fantastic capacity to focus on communities of people that are often overlooked.”

Constructed between September 2018 and January 2020, the Anandaloy center covers a floor area of 174 m² for rooms and 180 m² for the veranda. The building is made from locally sourced materials, including fired brick for the foundation, mud walls built using the cob technique (clay-rich soil is mixed with water, straw and a dough-like consistency and sculpted into walls while still wet), bamboo pillars and roof structure, a straw roof for the lower section, and a metal sheet roof for the upper part. The ramp, a dominant feature that “dances around the inner structure,” sparked conversation among the villagers. “People asked, ‘Why do we need a ramp?’ Then they thought about why it is important to include and provide spaces for everyone in the society. It’s beautiful how architecture can trigger these kinds of discussions,” Heringer reflects.

“… Within three months, you have 30 new tailors, but then these women end up in the textile factories that produce our cheap clothes under inhumane conditions.”

Due to land scarcity in Bangladesh, she also decided to add a second level to use as a workspace for female textile workers. She came up with the idea after witnessing severe environmental degradation, labor exploitation, and the misguided attempts of development aid to address these issues. “I noticed that the women were offered tailoring trainings because it’s one of the few professions available to them in that context,” Heringer says. Within three months, you have 30 new tailors, but then these women end up in the textile factories that produce our cheap clothes under inhumane conditions.”

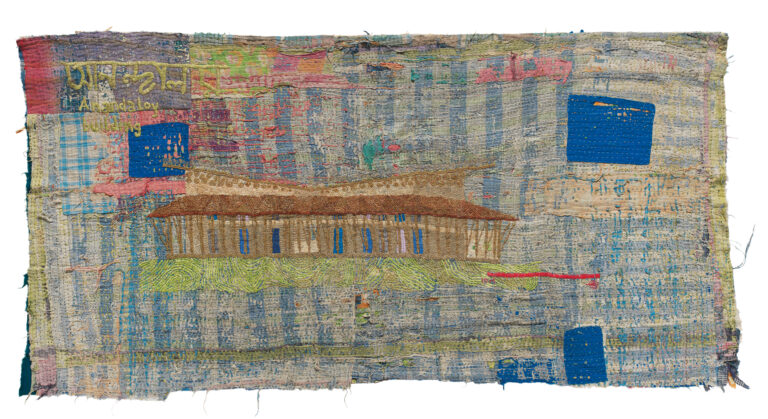

Wanting to create opportunities that would enable these women to stay in their village, Heringer, along with Bavarian tailors Veronika Lena Lang, Elke Burmeister, and long-term collaborator Dipshikha, established Dipdii Textiles, a label dedicated to fair textile production. “When it comes to urbanism, the driving forces for shaping those settlements in Bangladesh is the garment sector. I wanted to do something against this rural to urban migration,” she explains.

The employed tailors keep the traditions alive by hand stitching upcycled sari blankets and pillows. The role of a fashion label creator is somewhat unusual for an architect, as it keeps Heringer tied to the building after it’s been constructed. “It’s a challenge,” she admits. “But it is also beautiful when all your passions come together. Combining women empowerment with creativity and architecture is beautiful.”

Heringer’s dedication to women’s representation is deeply rooted in her purpose, which is also why she felt compelled to co-found DIVIA in 2021. “As a woman, I often feel like we have to fight on our own a lot of the time. Having hubs and groups of people to share [challenges] with is important.” But it’s more than that for her—it’s also about changing the system that has been favoring one specific approach over other useful alternatives. “What do we bring to the table that men cannot?” she poses the question before answering it herself: “A focus on the process, not just the outcome. It’s about care and empathy, which are also reflected in a good process. It’s about intuition and not just the facts, figures and research, or going for the most fascinating new tools, technologies and materials.”

“There are so many issues that you don’t face when you’re a man. It’s important to publicly discuss this because the building sector is a harsh climate. It’s important to have a network of women to say to: Is this happening to you too?”

The architectural field is currently structured in favor of her male counterparts. “There are so many issues that you don’t face when you’re a man. It’s important to publicly discuss this because the building sector is a harsh climate. It’s important to just, you know, be able to have a network of women to say to: am I completely paranoid? Is this happening to you too? How do you deal with it and what can we do to change it?”

Heringer has lectured widely both at universities and conferences and says that the masculine energy dominates the academia the most. She doesn’t let it deter her, though, and remains focused on her goals and the students, encouraging them to trust their inner voice through the method called “claystorming.” In this process, they work with large clay models, designing purely with their hands. “Typically, the higher a university tanks, the harder it is for students to let go of their intellect,” she explains. “This way, we train our intuition. The best projects are always those that follow the gut instinct and bring joy to the design—and you get feedback immediately.”

Over the years, Heringer has arguably proved better than anyone how modern and versatile building with clay can be, though the practice itself isn’t entirely new. “You know, we always think that mud is just a material for small African hut, but it’s not. We have examples where earth has been used for all sorts of structures—palaces, hospitals, temples, single farmhouses, even skyscrapers,” she says.

“Isn’t it your dream?” I ask, recalling her TED Talk. “To build a skyscraper made entirely of clay in the middle of Manhattan?”

She smiles. “Well, now it’s probably more a skyscraper in Accra. But the real question is: How high do you need to go? The height of a tree, like six or seven stories, where you’re still in contact with the street—that seems more fitting, so I wouldn’t necessarily call it a skyscraper anymore. But I would love to work in dense spaces because it would look beautiful.”

Heringer is selective about the projects she takes on, trying not to jump too much between continents and cultures and giving herself the time to adjust. “It’s never just architecture; it profoundly changes my life as well,” she says. Currently, she’s working on two sustainability campuses: one for the community in Tatale, Ghana and one in the Bavarian town Traunstein in Germany, for the Campus St. Michael. “It’s nice to do them simultaneously. Both are for the Catholic Church [the former was commissioned by the Salesians of Don Bosco, while the latter is being overseen by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Munich and Freising], so it’s essentially the same client.”

When I ask her about the future, she is optimistic. “I’m excited to continue to bring African elements to Bavaria and some of the learnings from here to Ghana,” she says. “And if we bring all the globally existing talents to the table, then I have a lot of hope for the future. We have this fantastic material underneath our feet. All we need is the creativity to use it.”

Photos of Anandaloy Center: Kurt Hoerbst

Photos of Dipdii Textiles Embroidery: Günter König