“An architect can’t be afraid of overwhelming complexity”:

Almut Grüntuch-Ernst on the award-winning hotel WILMINA, remaining curious, and raising a new generation of architects.

Almut Grüntuch-Ernst leads a dynamic life. As the co-founder of a successful Berlin-based architectural studio, Grüntuch Ernst Architekten, a professor at Technical University in Braunschweig, a hotel owner, and a mother of five, she adeptly juggles multiple roles and appears to navigate (at least from the outside) her busy schedule with ease and a calm demeanor.

Being surrounded by crowds is familiar to Grüntuch-Ernst, a reflection of her upbringing in Dithmarschen, a village at the North Sea coast. Sie grew up in a big family with parents and a younger brother, as well as grandparents, uncles, and cousins nearby. Amidst the communal lifestyle’s chaos, the vast fields and moorlands of Dithmarschen provided a sense of calm, while abandoned barns and places sparked a yearning for adventure and creativity. During her youth, she and her friends built caves and treehouses with timber.

Ever since Grüntuch-Ernst was a little girl, she found joy in nature and relished in the feeling of freedom. She believes that growing up in such a way—a circumstance she today considers a privilege—could be a significant factor influencing her choice to pursue architecture as a profession.

Her great-grandfather, whom she never had the chance to meet, was an architect from Stuttgart in southern Germany. But her genuine interest in the profession blossomed during her school years in one of her art classes. The teacher had cut up pictures of buildings and distributed one piece to each student, instructing them to recognize and extend the perspective lines behind it. Grüntuch-Ernst, who was accustomed to thinking and acting freely, found the exercise somewhat boring. “I just continued to draw the house differently. I enjoyed exploring all the many possibilities of how this one piece of a house could become a part of a larger house,” she says. “I thought that way was really fun.”

Her curiosity ignited a passion, and she pursued it diligently. She first embarked on her architectural journey by studying at the University of Stuttgart, then continued her education at the Architectural Association in London, for which she had earned a scholarship. This experience provided a refreshing contrast to the technical and structured education in Germany. Grüntuch-Ernst notes, “Studying in London was a nice challenge because I got to know a different perspective.”

Following her studies, she worked at Alsop & Lyall in London, where she crossed paths with her now-husband Armand Grüntuch. Both were contentedly charting their individual careers in Britain’s capital when, suddenly, on November 9th, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. “We immediately knew that exciting things were going to happen there, so we moved back to Germany soon after that,” she says.

Berlin indeed was full of hope, and its architectural future mirrored this sentiment. Big projects were envisioned as the two parts of the city were unifying again. It was an exhilarating but also challenging time for two emerging architects aiming to establish themselves with no notable references. Grüntuch-Ernst candidly admits, “Our beginnings were a bit counter-cyclical because we slowly started when the first building crisis hit Berlin.

Packing up her bags and leaving London for Berlin seems just another testament to her dynamic nature. Grüntuch-Ernst embodies a blend of analytical discipline and intuitive creativity—qualities that complement each other seamlessly but are rarely found balanced in someone’s personality.

“I want to remain open-minded,” she says. “This is indeed something that can wear off with age, but I am always curious and never think that we are so established as a studio that I know everything. We are still exploring.”

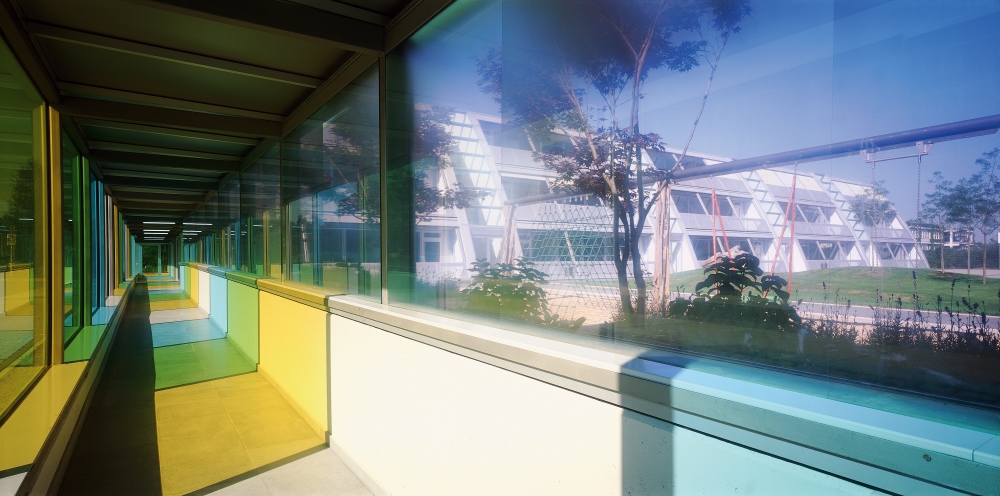

Taking on roles as research assistants at the HdK (today UdK) Berlin allowed both, her and her husband, to participate in architectural competitions and write assessments in their free time. In 1991, the couple co-founded their own studio Grüntuch Ernst Architekten and in 1993, secured their first project: a special needs school for disabled children in Berlin-Hellersdorf, commissioned by the Building Department. This type of building was a novelty for the former GDR.

“For two unknown architects, it was fantastic to win this competition,” she says. “But I believe it was a bit easier back then that it is now. These days, it is more challenging for young architects because you must have certain amount of experience to enter most competitions.”

The architects worked on this project with a great deal of empathy, taking into consideration the perceptual worlds of the students. They created a lighting design and employed color schemes that facilitated intuitive movement around the school.

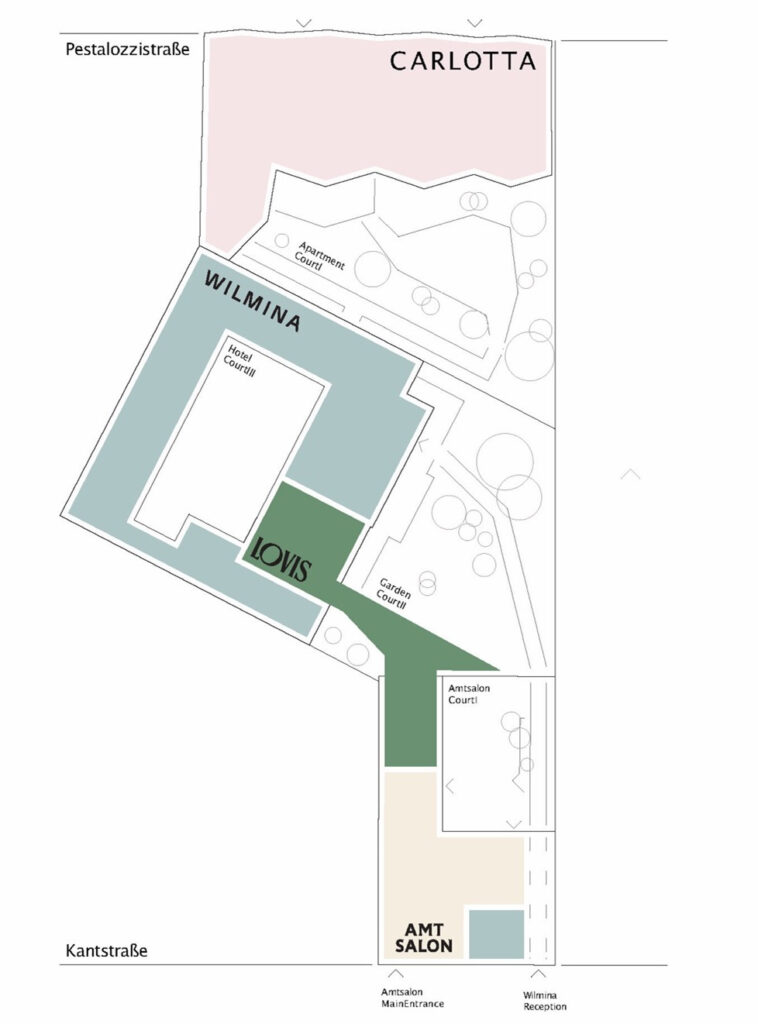

The studio remains inquisitive which is also evident in the types of projects that they do, always challenging themselves with new ideas and taking on different assignments. Their repertoire includes, among others, schools, cultural and public projects, as well as residential, office and commercial buildings. Just recently, they finished the Carlotta apartments—modern, quiet, and high-quality furnished flats that they designed for those who come to Berlin for an extended period of time. The apartments are located on Pestalozzistraße in the centrally situated district of Charlottenburg. The generously sized units range from 32 to 246 square meters and are flooded with natural light through their large, floor-to-ceiling windows. Most of the apartments feature spacious balconies that provide a magnificent view of the tranquil green courtyard.

From the Carlotta apartments you can see the ivy-covered wall of the former women’s prison now transformed to the hotel Wilmina, for which the studio received the German Sustainability Award for Architecture 2022. The hotel building, situated just beyond the bustling Kantstraße, is nestled within a housing block in Charlottenburg, so discreet that the architects and even the neighbors were unaware of its presence. “We lived in Charlottenburg for many years but never knew this building existed,” Grüntuch-Ernst admits. “It was a complete surprise.”

“These days, it is more challenging for young architects because you must have certain amount of experience to enter most competitions.”

After the German reunification, it was East-Berlin, with its derelicts and abandoned spaces, that was rich in empty areas and their untapped potential. Finding something like this in the West was a discovery worth pursuing.

After the original investor lost interest in the project, the architects, recognizing the historic and the future value of the place, acquired the property themselves. But the process didn’t come without its challenges. In fact, it was quite a somber affair: the building—that was listed and couldn’t be torn down— had many sealed-off areas with barbed wire fences, thick walls, high windows, and dark, cramped spaces. Not the best foundation for a hotel, so why turn it into one?

“We wanted to open the space to the people again but also find a balance where the history of the building is respected in all its complexity,” says Grüntuch-Ernst. “We thought about the ‘enchanting’ qualities of the places and how we could elevate them.”

It’s true, the whole complex does have a romantic and charming feel to it. The front building— a former court that serves as the entrance to the building complex—has been revived as an art and cultural space called Amtsalon.

Going deeper into the complex you find yourself in a quiet garden with wild ivy covering the façades. In the former lock yard, which once served as the access to the cell blocks, you’ll find the hotel’s restaurant, Lovis.

The main entrance of the hotel was created by expanding a window opening into a door in the garden courtyard.

The hotel offers 44 rooms and suites, a roof terrace, a library, a fireplace lounge, a bar, spa, and a gym. One of the guiding elements in the conversion was the use of light. The goal was to open up the spaces and create a flow through the rooms that used to be isolated— some were only 1,43 meters wide and hard to access. The former cells underwent a transformation into cozy rooms, with some preserved in their tiny form, while others were combined for a more spacious experience.

“Typically, architects add and assemble materials, but, in this case, we worked in a very subtractive way. We removed things and, in doing so, highlighted new spatial relationships and larger, brighter rooms,” she explains.

“When you entered the building before, you felt somewhat small, hunched your shoulders, and perceived it as oppressive. Essentially, we turned the whole physical experience around, so you somehow feel more inclined to follow the lights. These are perceptual psychological distinctions, even though the elements are still the originals,” Grüntuch-Ernst concludes.

In the former cell wing, where the atrium spans five levels, light was also used as an installation, with glass pendants suspended from the ceiling. They stretch so far up you can’t really tell where they begin. And thanks to the vitrification, it is hard to differentiate which ones are real and which are reflected.

Another aspect that naturally comes to mind when considering the creation of retreat spaces in a location formerly utilized for oppressive purposes is the instinct to remove the bars. However, upon closer examination, the architect notes that this was not necessary.

“The monument authority had already said yes to removing them, but because we had augmented the window jambs, the bars now ended midway and didn’t seem bothersome anymore. In certain bathrooms, the windows were left as they were.” So were the doors that were all kept original.

To cater to guests desiring larger (and therefore pricier) accommodations, Grüntuch-Ernst added a penthouse atop the building with clean lines and floor-to-ceiling windows offering great views over the courtyard. Under the supervision of the monument authority, they utilized the existing sloped glazing, opening it up to fashion the four new rooms. The architects employed special panels to ensure a seamless and homogeneous connection between the two parts. The Lloyds Hotel in Amsterdam served as inspiration. “A space that combined different hotel stars in one house sounded appealing to us. I thought it was an interesting concept that allowed for a mixture of guests,” Grüntuch-Ernst says.

I like the idea of creating something new that adds a refreshing element to an already existing structure but wonder if there is a way for guests to connect with the building’s past. The history of a place like this is meant to be preserved but can it also be experienced?

“The history is rather profound, it’s not something you can casually display in a breakfast lobby,” she says. “I also expect people to take a moment to truly engage with it.”

There is a former cell behind the rear staircase that is open to visitors and that was left in its original state. It stores all the collected documents regarding the history of the house. As a guest, you can inquire about the key and enter this room to engage with the material.

“We are currently considering ways to better connect and digitally represent the research from this location, and we are already in discussions with various institutions about this. This would make the information more accessible,” Grüntuch-Ernst says.

Some of the notable hotel guests have included Rebecca Donner, the author of the critically acclaimed book All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days about her great-great-aunt Mildred Harnack who had been imprisoned here and executed in 1943. “She wrote us once that she was interested in visiting the place not expecting to want to spend the night here. She is a returning guest of the hotel now,” Grüntuch-Ernst says proudly. For the German author Norman Ohler, who wrote the book Harro & Libertas about the two Nazi regime fighters, they organized a public reading in the courtyard.

The guests who wish to explore the history of the place privately can peruse the architects’ book Wilmina, which is displayed in the rooms. The book includes an excerpt from Ulrike Edschmid’s autobiographical story, who was imprisoned here at the end of the 1960s. As a member of the radicalized student movement, she was accused of killing a police officer but could eventually prove her innocence. “Edschmid did visit the hotel more than 60 years later,” Grüntuch-Ernst says.

As I listen to her speak about the project and the weight that it carries, both in terms of history and responsibility, I am impressed by her willingness to take it on with no prior experience in the hotel industry. It is a risky endeavor, but, as with most things in her life, if there is no better alternative, Grüntuch-Ernst would rather bet on herself. Initially, she thought they would focus on the architectural transformation and then bring in professionals for everything else. But when the discussions with potential tenants raised strange questions, such as wanting to capitalize on the theme of the hotel being a former prison, she decided against it.

“We also spoke to other hotel operators who were very interested in the place, but they were turned off by the fact that we only have one elevator—usually, you need one for guests and a separate one for the staff,” she explains. Grüntuch-Ernst, however, found the idea of interaction between staff and guests appealing. So the architects decided to take charge themselves, seeking assistance from their children. Their son voluntarily paused his studies in mathematics and biology in London to return home and help with the opening management. One of their daughters, equipped with a hospitality degree, contributed her expertise and know-how to crucial decisions. Another daughter managed their Instagram account, while the youngest aided in flower pressing for room interiors’ decoration. The original plan was to open in May 2020, but due to the pandemic, the opening was delayed by two years. They have now been open for 1½ years and have assembled a team that also oversees the event location in the court building.

Receiving the Sustainability Award for this challenging project seems like the icing on the cake, a recognition for their hard work and effort. Given that the project involved conversion rather than new construction, it led to reduced CO2 emissions and minimized construction waste. The reuse of many materials has enhanced the building’s sustainability, resulting in reduced reliance on technology. The courtyard offers acoustic protection, enabling natural window ventilation even during the night. The extensive greening in the courtyard fosters biodiversity and contributes to a delightful microclimate.

Given Grüntuch-Ernst’s roles as an architect and hotel owner, one might find it hard to imagine she has energy for anything else. However, make no mistake: her commitment to teaching is equally, if not more, demanding. In 2011, she was appointed as the director of the Institute for design and architectural strategies at the TU Braunschweig, and she’s there half of the week. It’s the fall holidays as we speak—that’s why she has time for me, she says jokingly. “Every architect has their specific focus, so, of course, you want to impart that to the students,” she begins. “But it’s also important to assist them in maintaining their individuality, aligning it with their approach.”

One of the topics Grüntuch-Ernst has been focusing on this semester is school buildings, exploring how educational spaces can provide a stimulating atmosphere for learning. “Does the architecture convey a message or is it some kind of bleak makeshift measure?” she asks rhetorically. “Is the space somehow exciting and sensorially demanding? How can we provide students with an experiential space before they are completely digitally distracted? Of course, there are also economic and financial constraints to consider, but how can we economically create and maintain a living space?”

She is also intrigued by the concept of horticulture, emphasizing how meaningful it is to consider living plants and architecture as an integral system.

“As an architect, you cannot be afraid of overwhelming complexity. In fact, there must be courage to contribute to it.”

“Every building is part of the ecosystem, and that needs to be embedded in the mindset first,” she explains. “What do the surfaces do to the urban space? The same can be asked from a social perspective: what are the public spaces, what are the private spaces, and how can that be negotiated? How can it be inviting but still feel secure—it’s not something that can be easily answered, so it’s important to work with different disciplines.”

Almut Grüntuch-Ernst seems thoughtful and intentional about the ideas she imparts to the new generation. As the year draws to a close, it is only natural to contemplate the future—what else does she wish to dedicate more time to? In true Grüntuch-Ernst fashion, she has a myriad of questions and plans to remain curious, always ready to embark on a new adventure, face a new challenge.

“There is something that increasingly interests me: the building materials that surround us. Where do they come from? Can they be reused, if not, where do they end up? There is a desire to understand more about the origin of these building materials but also learning about their influence on our health. We know there are building materials officially declared as harmful. How do we actually dispose of them and where? And how do we ensure that we do not continue to use such substances for special waste landfills? More mindfulness will also be necessary in that regard. I think this whole chapter is still somewhat in the dark. But as an architect, you cannot be afraid of overwhelming complexity. In fact, there must be courage to contribute to it.”

Undoubtedly, she will do her part to help bring it to light.

Text: Veronika Lukashevich