Tatiana Bilbao

on 20 years of doing architecture “with people, for people, on behalf of people”

One of Mexico’s most visionary and sought-after architects, TATIANA BILBAO, speaks to Veronika Lukashevich about building a monastery, the importance of a diverse team, motherhood, and the simple joys of lazy Sundays

Tatiana Bilbao has Covid.

On a Thursday evening in February in central Mexico City, I am preparing to speak to one of the country’s most prolific architects when her marketing team emails to inform me that she has tested positive for Coronavirus and will not be able to meet me. But as disappointing as this is, Bilbao’s strong sense of commitment won’t allow her to cancel on such short notice. She suggests I tour her studio instead and we speak via Zoom right after. I gratefully agree.

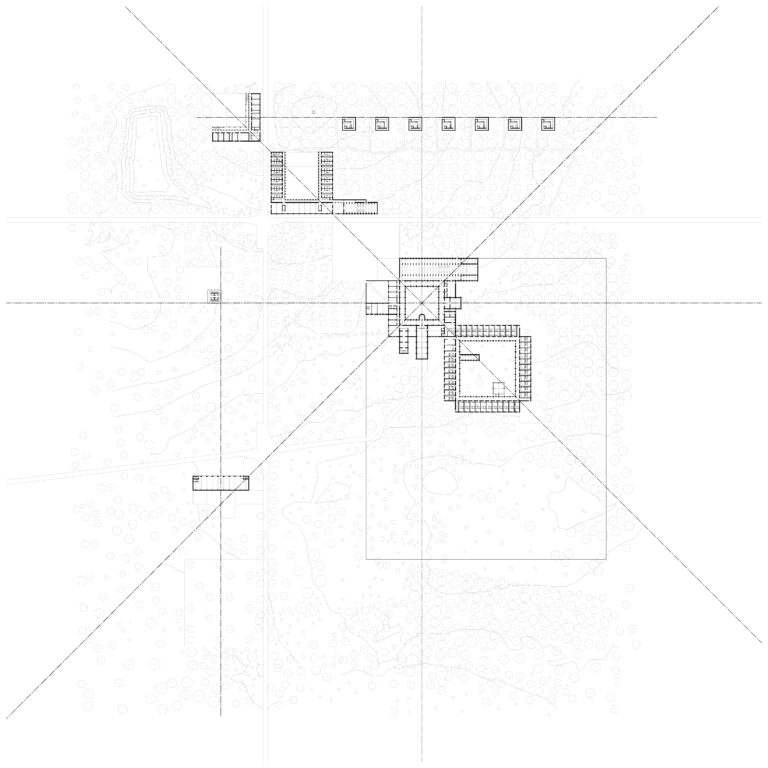

The next day, I am guided down a light-filled, colorful corridor to a room with glass doors adjacent to Bilbao’s office. As we pass an open office area (and a team of about 30 people hunched over their desks), I notice a wall covered with collages of photos, renderings, and drawings of a monastery she is currently building in Germany. I feel a surge of excitement—this is the project I am most eager to discuss with her.

Bilbao greets me cheerfully from the other side of the Zoom call, giving no hint that she’s been unwell. “I have had very few symptoms, so I feel fine,” she reassures me, then adds with a smile: “But I have nowhere to be now, so I have time for all your questions.”

“We’re never going to change anything just by saying it’s wrong. I always see failures as obstacles and look for ways to trespass them. As architects, we must rely on optimism.”

I indeed have many. Since opening her eponymous studio in 2004, one of the first women architects to do so in Mexico, Tatiana Bilbao has completed projects all over the world. Her work has been celebrated for her humanistic approach and sensitivity to cultural and environmental contexts—making her a leading figure in contemporary architecture. Known for integrating social values into her designs, Bilbao aims to create spaces that are both functional and emotionally resonant.

In a career spanning over 20 years, she has garnered international acclaim for projects such as the Sustainable Housing Model, which introduces affordable living solutions in Mexico, and the award-winning Culiacán Botanical Garden, a harmonious blend of art and nature. Last year, she completed the Sea of Cortez Research Center, an aquarium located in coastal Mazatlán, in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. The center aims to convey our connection to nature and demonstrate how architecture can help reintegrate us into our ecosystem.

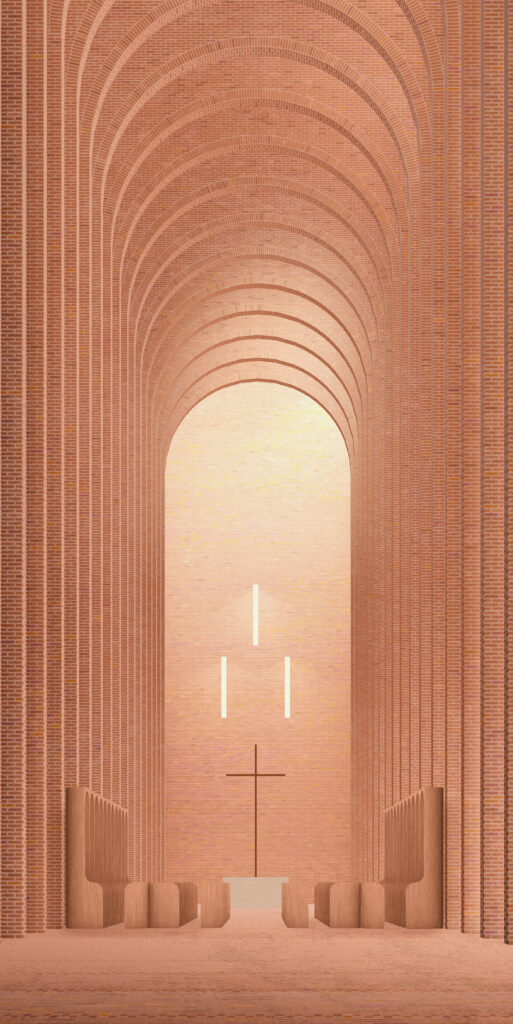

Few projects, however, can rival the ambition of her current endeavor: the new Cistercian monastery in eastern Germany. This monumental structure, the first of its kind to be built since the Middle Ages, is set in a secluded forest near the village of Treppeln (Neuzelle) in Brandenburg. “I have always said it is a lifetime project because it’s going to overpass my time [on Earth],” she says when I ask her how she’s processing this huge undertaking. “It’s [divided into] five phases, so it’s very ambitious, and I hope I’ll see at least two being built. But, for sure, it’s a life changing project in many regards.”

In what way? “It has changed my perception of time. The monks don’t live in the same time frame we do; for them, life is eternal, so they’re not anxious about when the building is going to be done,” she explains.

The close interaction with the monks inspired her to reflect on longevity and the type of architecture we should be building. “Architecture is the representation of its time, but I’m not sure how aware we are of what that means, especially in contemporary society,” she begins. “I look at Dubai, for example, and it makes me wonder what of it will still be here in a thousand years—and I don’t see much.”

Personally, Bilbao sets out to create buildings that can sustain the changes they will face throughout the years. “I always create architecture based on lives that haven’t passed through it [yet]. Building a monastery on these terms has helped me to think of time more profoundly. I think that it is a huge responsibility.”

From our conversation I realize that such leadership, especially for a project of this caliber, can only be successful when paired with the humility to recognize that nobody can do it on their own. Thankfully, Bilbao has never been the type of architect to shy away from collaborating with her peers. On the contrary.

“I need them”, she says. “It’s a very selfish thing. Architecture has never been an individual act. If I were the only one to imagine how someone should live—poor them!” She widens her eyes for emphasis. For Bilbao, this also means surrounding herself with a culturally diverse team. “We will create many more opportunities for opening paths, accept more people, and discriminate less, if we have people with diverse visions on life sitting at the table.”

Bilbao is adamant about the importance of honoring the Cistercians’ deep connection to their living space and ritual practices. To ensure the new design aligns with the monks’ vision, she is collaborating with Dogma studio from Brussels, an architectural office experienced in monastic life, and MAIO from Barcelona, who she believes understand the balance between individual independence and community living. Together, they pay close attention to detail, from the structural layout to the acoustics, which are essential for the daily prayers and chants.

While faced with the challenge to create a modern building with such a rich historical legacy, Bilbao also went through a deep personal change.

“The project has impacted my relationship with faith incredibly. I come from a country that has a very difficult relationship with Catholicism. Our country was colonized through religion—it was the tool used to transform this territory into the Spanish regime,” says Bilbao, whose grandfather was the Spanish architect and politician Tomás Bilbao Hospitalet. When she first met the monks, Bilbao admits that her view of them could have subconsciously been influenced by her perception of the Catholic Church. Visiting the monastery, however, showed her that faith transcends the institution. “Faith is deeply personal. What I found beautiful about the monks is that they live their lives in their own way, without imposing their beliefs on others. So that was a very interesting process for me.”

Hearing this, it seems that Tatiana Bilbao approaches every project with deep care and empathy for diverse ways of living. She describes architecture as “a labor on which we rely to exist.” This also means, which says, deciding which projects to pursue and which professional requests to decline.

“For me, it is very difficult to understand how to do architecture only by thinking about composition, geometry, colors, or aesthetics. [We need] those tools, of course, but I always thought of architecture [as something to be done] with people, for people, on behalf of people. That is the overarching principle that really directs what I do in full.”

At the beginning of her career, Bilbao made these decisions intuitively, guided by a clear set of personal values. Today, her studio follows a written protocol outlining their principles and what they represent as an office. “We do not undertake any projects that prioritize the extraction of capital at the expense of people. No way,” she says, firmly.

“We will create many more opportunities for opening paths, accept more people, and discriminate less, if we have people with diverse visions on life sitting at the table.”

Bilbao is clear on what she stands for, but she is not naïve. She understands that architecture does not exist in a vacuum and is always intertwined with the larger system in which we live. Naturally, this means that any architectural pursuit hoping to effect change must respond to this reality. “We’re never going to change anything just by saying it’s wrong. I always see failures as obstacles and look for ways to trespass them. As architects, we must rely on optimism.”

Such insight could be expected from someone with decades of experience, yet Bilbao acquired this wisdom quite early in her career. After graduating from Universidad Iberoamericana in 1996, she began working for the Ministry of Urban Planning and Social Housing in Mexico City. As a young woman driven to improve accessibility in the city center, she believed she had landed her dream job. However, over the next two years, she quickly became disillusioned by the sobering reality and stifling bureaucracy of her tasks, none of which, she says, had anything to do with creating spaces for the city. Bilbao left the job to bet on herself instead but remained close with the Director of Urban Planning to help her put together lectures, which was Bilbao’s introduction into the academic world.

Then things unraveled quite organically: Soon after, she ran into a former friend from school; together with two other colleagues, they formed a practice. After four years, she was ready to open her own, clear about the mark she wanted to leave on this world. To pass on her knowledge she acquired though the years, Bilbao later accepted visiting scholar positions at renowned universities such as Yale and Columbia, and has lectured at institutions including the Royal Academy of London, Museum of Modern Art, Harvard Graduate School of Design, and Princeton. She has also won plenty of awards, including the Kunstpreis Berlin (2012), the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture Prize by the LOCUS Foundation (2014), and the Richard Neutra Award (2022).

“What I found beautiful about the monks is that they live their lives in their own way, without imposing their beliefs on others.”

No doubt, Bilbao’s success is hard-earned, but she also attributes part of her tenacity to her identity, saying that being an architect is “in my blood.” She means this not only in the sense of growing up in a family of distinguished architects but also as a fundamental part of being human—and, specifically, as a woman.

“Even our bodies are architecture,” she tells me.

I am intrigued and ask her to elaborate.

She begins by recounting a story about fellow architect Isabel Martínez Abascal, who once gave a lecture at ETH Zurich as part of Bilbao’s series on architecture as a form of care. “Isabel said: ‘I spent a lot of years mastering architecture, but I never really understood what it was until I became architecture.’ She meant until she became pregnant. And I was like, yes, because [this experience] really allows you to understand the importance of a protective shield.”

She continues: “When I had my children, I understood much better how much we need each other to exist. For me, [motherhood] shapes architecture, because it gives us the possibility of relating to each other and existing on this planet.”

It seems impossible, wrong even, to try and separate Tatiana Bilbao from her identity as an architect, a role that is so integral to who she is. Still I wonder: beyond her busy schedule and intercontinental travels, what else fills her cup? Is there such a thing as a lazy Sunday for her?

As a matter of fact, there is. She paints the picture: “My husband would be cooking, and I would just hang in the house, fixing something or organizing a closet. The kids would be playing, and I’d probably go after them, saying, ‘You have to pick [your stuff] up.’” She smiles. “Then we’d listen to some music or go to the market. And I’d make a dessert.”

This reminds me of a story I read online where she mentioned that in an alternate reality where she isn’t an architect, she would probably own a bakery. “Is that true?!” She nods.

“But the thing is that I also really like to cook, and I married someone who loves it. It’s really his world now,” she says, telling me how her friends, who used to call her for recipes in the past, now try to reach her husband instead. “And I’m like, what?” she laughs.

Although trying one of Bilbao’s beloved desserts (“I bake Christmas cookies, sweet bread, and tarts”) would certainly be a memorable experience, I’m glad she chose architecture as her career, given all she has achieved in the last two decades. When I ask her about this year, which marks the 20th anniversary of her studio, she surprisingly seems unaware of the fact. I want to know if she’ll take some time to reflect on her achievements, but that’s not really Bilbao’s style. “I never believe much in those things. I don’t think in terms of anniversaries.”

She pauses then adds thoughtfully: “Past, future, presence—you just keep going.”

An interesting fact about Tatiana Bilbao’s approach is that she prefers collages to computer visualisations and renderings, as they help her stay creative and encourage collaboration during the design process. Above you can see some of her creations for the Sea of Cortez Research Center in Mazatlan, Sinaloa, Mexico. Credit: Tatiana Bilbao ESTUDIO.