WORLD WATER DAY

“Water is not a commodity”:

architect und urban designer Loreta Castro on changing how we think about our most important resource

Chances are you’ve seen it dominating the international headlines lately. Mexico is facing a water crisis, with warnings of an impending “day zero” when taps could run dry in its bustling capital, Mexico City. But just how likely is this scenario?

“It could happen if we are not able to stop it from happening,” says Loreta Castro, the Mexican architect and urban designer, plainly.

It’s 7:45 a.m. (Mexico time) on a Tuesday in early March, when Castro and I meet via Zoom to discuss Mexico’s ongoing water crisis. The co-founder of the architectural and urban studio Taller Capital is the perfect person to speak on this, given her focus on water management strategies in the country. Clearly, I am not the first journalist to think so, as Castro currently finds herself in high demand, with numerous international news outlets seeking her insights on the matter (hence the early appointment). Despite the current surge in international interest, the issue is longstanding, and Castro’s expertise is extensive. It stems from decades of research and hands-on experience navigating Mexico’s complex water culture, characterized by flooding and water scarcity.

With a population of nearly 22 million people, Mexico City ranks among the world’s most populous cities. As such, it faces increasing water needs, with at least 250,000 residents living without connection to the water network. These numbers are particularly alarming given that historically, Mexico City was known as the “city of water”—originally built by the Aztecs atop a high-altitude lakebed—but then the Spanish drained it following their conquest in the 16th century. Still, the city of water will remain loyal to its name, Castro says, given that the lakebed, even if emptied, will always refill naturally. “We just have to learn how to manage it.”

“We need to understand the cycle of water during the different seasons, rather than see it as a beautification gadget.”

About 70% of Mexico City’s water supply currently relies on underground sources known as aquifers that have been excessively drained over the years, causing the ground to sink. The remaining 30% is sourced from the Cutzamala System, a network of canals, tunnels, dams, and reservoirs. The city’s infrastructure is outdated, with leaking pipes leading up to 40% water loss. But one should not be so quick to dismiss it, Castro argues, given that, flawed as it may be, the system has been essential in sustaining the lives of 22 million people. Instead, the new approach should focus on integrating additional practices (not replacing the old) to ensure the long-term functionality of the city. A challenging task, Castro confirms, “but perspectives can be changed.”

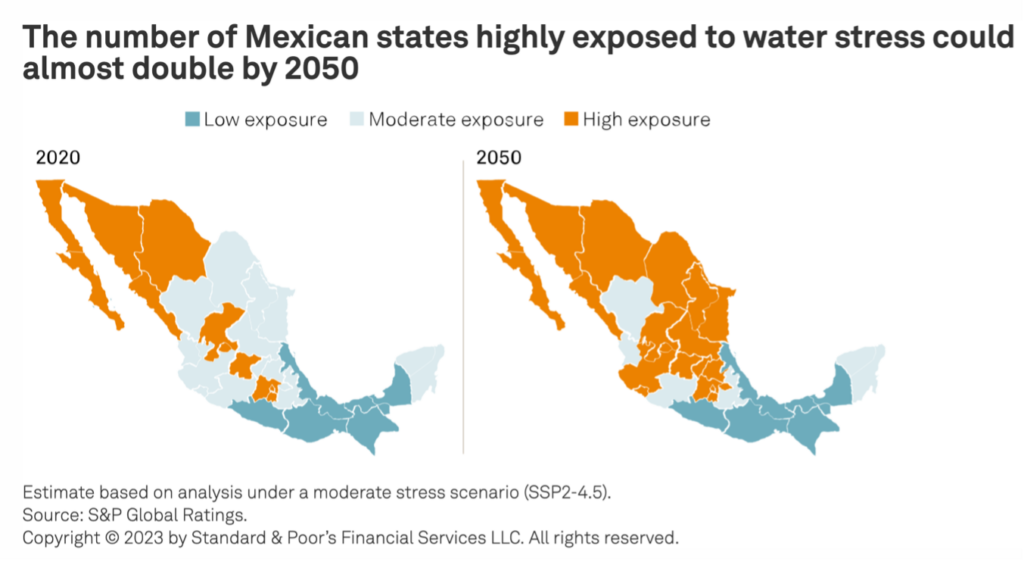

As they should, given that the issue extends beyond the capital city, affecting the entire country. Some experts predict that by 2050, the number of Mexican states facing high water stress could double, potentially reaching 20 states. In times of crisis, people tend to rely less on the government and take matters into their own hands. One of such standout initiatives is Isla Urbana, a team of engineers, designers, and sociologists dedicated to rainwater harvesting. Since their inception back in 2009, they have been targeting impoverished communities to install rainwater harvesting systems in people’s homes and currently report an annual harvest of 191 million liters. “The idea is to have a city where, during the rainy season, everyone is collecting rainwater through their rooftops – capturing it, channeling it and using it in their homes and allowing that recharge to happen in the city,” said Isla Urbana’s co-founder Renata Fenton in an interview with One Earth back in 2019. But while such efforts are commendable, Castro (who has worked with Isla Urbana in the past) says that the issue lies deeper and must be addressed at its core. “It’s about changing the water culture,” she says. “On the domestic scale, we need to learn to love water, on the city scale, we need to understand the image of water not as an aesthetic element, but as part of the city and our lives.” She adds: “Water is not a commodity. We need to understand the cycle of water during the different seasons, rather than see it as a beautification gadget.”

Together with her co-founder Jose Pablo Ambrosi, Loreta Castro centers her research and work precisely on this issue, introducing new water management strategies that are implemented through infrastructural public spaces. An example for this approach is demonstrated in the Bicentenario Park, located on a hillside in Ecatepec within the greater Mexico City urban area—a region known for its high levels of poverty and crime. In revitalizing the park, Castro reintroduced the concept of terraces, originally utilized for agriculture in the 1940s and 1950s. These terraces, spanning 600 meters and bordered by concrete walls, are filled with tezontle—a porous volcanic rock native to the area and known for its ability to absorb and retain rainwater—that gradually percolates and eventually replenishes the aquifers. Serving a dual purpose, the terraces also function as a public space while connecting the residential areas at the top and bottom of the slope.

“That way of making the landscape work as an infrastructure has been really important because there is no need to spend energy, there is no need for big maintenance. It’s just letting the landscape perform as it is,” Castro says.

Taller Capital was originally commissioned by the government to refurbish an existing park and provide football courts, but they quickly realized that there was potential for more. “The hillside is the best place to infiltrate water, that’s how the cycles work,” Castro tells me. The park was developed in two phases. The first section, covering eight hectares, was inaugurated in 2021, and residents have been using the terraces for cultivating flowers and vegetables ever since. “For us, this is the best image ever,” Castro says with enthusiasm, as she shows me photos of neighbors gardening. The second section, which includes a regulation basin, a skate park, and a baseball playground, was inaugurated only three weeks ago at the time of writing. “We’ll see how it performs.”

The region is a familiar sight to Loreta Castro, as she is no stranger to rugged environments, having grown up in the Pedregal, an area characterized by large, rocky landscapes in the southwest of Mexico City. “My school and the university were also in the same neighborhood, so I spent my entire youth in this type of vegetation, in between these rocky gardens,” she says. “Landscape is very important there, it shapes your mind.”

Loreta Castro was born into a family of engineers; her uncle, who was an architect, designed her childhood home. But it wasn’t until she had the opportunity to travel to Florence, Italy as part of an art history excursion during high school that she truly fell in love with architecture, specifically with the dome of Filippo Brunelleschi. “The very fantastic thing about visiting that church is that you are able to go up the cupola in between two shelves of brick,” she says. “But also understanding the constructive system of the dome, how it holds by itself. It really opened my eyes to see the world differently.”

Inspired by this trip, Castro then started her architecture studies at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) in Mexico City, which soon led her to a three-year tenure at the USI Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio. During her time in Switzerland, she was mentored by none other than Peter Zumthor (who also supervised her diploma project), along with Mario Botta, Aurelio Galfetti (the dean of the school at the time), Luigi Snozzi, and Livio Vacchini. She fondly recalls her time at the school as “the best experience of all”, highlighting how its intimate size fostered a close-knit community among students and engaged teachers. The hands-on approach to learning had a profound impact on her architectural aspirations. Castro says studying with Zumthor may seem “cliché” today, but he was instrumental in her understanding of architecture as “a way of living freely with all your feelings.” After returning to UNAM to complete her graduation, she found support in Humberto Ricalde, who not only guided her but invited her to teach alongside him. “It’s fantastic how you start finding these people that help you on the way,” she says.

“[Women’s] untold history needs to be registered: what happened, what is taking place today, and what will be. Diversity in Architecture is one such very relevant voice—an organization by women, registering and telling the history and the stories of women in architecture.”

It’s impossible to overlook, as Castro herself acknowledges, that all her important mentors were men. “That’s the thing with architecture,” she says. “When I was a student, there weren’t that many female professors.” She pauses, then continues. “Maybe that’s the goal for our generation—having to change these things. But in my case, men have always been supporters and not detractors.” This nurturing environment traces back to her father, who was always deeply concerned with his daughter’s well-being. “My dad was the one that really encouraged me to go to Mendrisio. He was always thinking about me and my sister, about making us as autonomous as possible,” she explains, noting that his protective efforts led both her and her sister to attain black belts in karate. “My dad used to say: you need to be able to protect yourself.”

This sentiment is grounded in the grim reality of Mexico, where violence against women persists as a significant issue. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 66.1 percent of all women aged 15 and older have experienced some form of violence. During a visit to Mexico City in February, I noticed the existence of designated wagons for women and children in the subway. In multigendered cabins, there are multiple indications warning against sexual assault. The introduction of women-only wagons has led to a 26% reduction in cases of sexual harassment, however, insufficient checks at various stations continue to be a problem. As I share this, Castro is not surprised. “I’ve been very blessed, but it doesn’t mean [violence against women] is not happening.” She therefore advocates for women’s rights and supports initiatives promoting their work in architecture and design.

“I am convinced about women, as space designers, being involved in the making of cities ever since human groups became sedentary. We have also been able to give cohesion and identity to our communities, when nomadic, through other ephemeral design elements. That untold history needs to be spoken and registered: what happened, what is taking place today, and what will be. Diversity in Architecture is one such very relevant voice—an organization by women, registering an telling the history and the stories of women in architecture,” she says.

Loreta Castro speaking at her alma mater Harvard Graduate School of Design

When Loreta Castro pursued her Master’s degree in Urban Design at Harvard University, she encountered a program that, much like her previous experiences at UNAM and at USI in Switzerland, was predominantly male-oriented. Out of a group of 30 students, there were only five women, and most of the professors were men in their 60s and 70s. “It was very hard for us women, to stand there and make a point and not be wiped out,” Castro reflects. “My first year was a disaster and then in the second year, something happened. Maybe I got used to it,” she says with a smirk. “The school is hard. You need to be able to swim in the shark tank.”

But something significant did happen. It was during her time at Harvard that Castro made the decision to focus her work on water—a choice that would profoundly shape the trajectory of her career. “I was thinking, ‘What [impact] can I do in my city?’” The water issue immediately came to mind and she secured a prestigious grant aimed at researching water management in cities around the world. She embarked on this ambitious project alongside her current professional partner Jose Pablo Ambrosi, and over the course of two years, they both traveled to China, India, Bangladesh, Peru, Brazil, Italy, and the Netherlands, studying people’s water cultures—a fruitful time, filled with numerous realizations and “aha”-moments. “Access to water is a human right, but it doesn’t mean that access to water in Switzerland, in the middle of the Alps, where there’s a lot of clean water flowing all the time, has to be the same as access to water in the desert of Chihuahua in Mexico,” she says. Our minds however, as Castro explains, tend to think that way, when in reality, the focus should shift elsewhere. “We need to learn from the territory to understand how that access to water needs to be given.”

Her project Colosio Embankment Dam, built in the 1960s in Nogales, right at the US border, stands out as a prime example of meticulous site examination. Commissioned by the government, Taller Capital was initially tasked with designing a park adjacent to the Represo Colosio but proposed transforming the existing basin into a recreational and public space instead, ultimately winning the 2022 MCHAP.emerge Award for this project.

“If you look at Roman or prehispanic Mexican architecture, there is a very important component of it working as infrastructure. And that’s where we should move the profession towards.”

“The water body used to be seen as a dump and it carried all the wastewater from the [surrounding] houses”, causing frequent flooding and erosion of the dam. To address this problem, the team collaborated with UNAM to redesign the space into a terraced landscape. Depending on the season, different levels are either submerged or available to the community as sports grounds, playgrounds, and gardens. A proper spillway ensures the controlled discharge of excess water from the settlement. The installation of illuminated gabion pathways and seating areas around the water enhances the community’s perception of the area, creating a safer environment. The focal point of the Colosio dam is now a sports facility with a distinctive triangular roof. Along with basketball courts, the building has fostered the creation of local teams and raised new activities for the inhabitants, promoting social life in the area. “Now people see the lake as an asset,” Castro says, reflecting on how the residents have started to engage in the tradition of tequio (cleaning days) by taking daily turns to collect trash and coming together on Saturdays for a collective cleanup—a true shift in water culture.

Loreta Castro attributes a big portion of this success to her collaboration with her alma mater UNAM. “Our research was the main part of how we were able to make it happen,” she tells me. From 2011 until 2018, she held a thesis seminar on issues regarding water management at the university, where she continues to teach today, leading a project on migration alongside her colleague, friend, and fellow architect, Gabriela Carrillo. Castro believes in providing the students with the right and reflected information to help sustain the environment. “It’s very important that we [separate] architecture from luxury,” she tells me. “In schools we were taught how to design museums and hotels and libraries but not how to understand the entire urban fabric as our space of action.” For her, architecture is a service. “If you look at Roman or prehispanic architecture, there was a very important component of it working as infrastructure. And that’s where we should move the profession towards.”

Next semester, Castro will teach at her second alma mater Harvard Graduate School of Design and at Chicago IIT School of Architecture, focusing again on migration by “intertwining landscape and the city”. She is also currently engaged in a project commissioned by the Swedish eco-focused foundation re:arc institute, funded by IKEA Foundation, which operates at the intersection between climate change, social conditions, and architecture. “It’s supposed to start construction within a month and a half, which is fantastic,” Castro says.

The project is an extension of their work from two years ago when Taller Capital transformed the historic downtown of San Lucas Xolox in the north of Mexico City. The construction of the new nearby airport had disrupted the natural flow of rainwater, leading to frequent flooding and therefore prompting Taller Capital to intervene, slowing down and channeling rainwater within the city center. This was achieved through the use of local volcanic stone to create small steps, slopes, and paved areas. Throughout the process, the team engaged with the community, conducting no less than 15 town meetings to work out a solution that satisfied all groups. The third phase, which Taller Capital is embarking on this year, once again places the local community at the forefront. Together with the ejidatarios—the local landowners—and the local Potable Water System, the studio has developed strategies for runoff management and flood control, integrating water into public space rather than simply diverting it away. Known as “Pooling Xolox”, this initiative will be built on a communal site, creating a water management infrastructure that redistributes runoff across agricultural land. The water is used locally and is incorporated into the public realm, presenting a more sustainable and cost-effective measure to piping methods. By repurposing water for agricultural irrigation and creating communal spaces for recreational and cultural activities, Pooling Xolox effectively mitigates floods while enhancing community resilience and wellbeing. “Xolox could become an example for landscape and urban design, integrating public life and water management in the Valley of Mexico,” Castro says.

Public projects like these are not always easy to implement, as they typically rely on government funding, which often entails high levels of uncertainty and bureaucracy. Having faced her share of challenges in securing government funding in the past, being financed by re:arc offers an alternative approach “to solving water issues”, Castro says. (Her project La Quebradora, the accessible water retention and treatment complex in Mexico City, took eight years to complete, having been halted multiple times due to changes in government). “It shows us that there are other ways of doing things,” she says. With the new presidential elections coming up in June, new changes on the governmental front are to be expected but Loreta Castro remains positive. “I feel hopeful because every time I dealt with the government, it’s only been getting better,” she says with a laugh. Does this unwavering optimism also extend to Mexico’s water crisis? Absolutely. Her work has shown that people are gradually recognizing their responsibility in the issue and are generally open to changing their ways if they feel connected to the environment. “We want to show people that landscape has the power to manage water and that these places need to be taken care of,” she says. “I think it’s been working.”

Author: Veronika Lukashevich