“We need complex problem solvers who see the bigger picture”:

Marina-Elena Wachs on her insatiable curiosity, interdisciplinarity, and “the multisensory experience”

Dr. Marina-Elena Wachs is a true jack-of-all-trades. She embodies a diverse array of roles: master tailor, industrial designer, studio owner, professor, and consultant, to name just a few. Wachs speaks to Veronika Lukashevich about creativity, the compromises one makes in motherhood and career, and developing a humanistic perspective in our rapidly digitizing world

It’s an early morning on the last day of August, and the heat in Berlin is slowly subsiding as Marina-Elena Wachs and I meet for our interview. She greets me warmly, dressed in an elegant black vest paired with long white trousers that beautifully complement her slim figure. It is undeniable that she has a keen eye for impeccable fit; but what may not be immediately apparent is that her outfit is not a matter of chance but rather the result of a finely honed skill: Marina-Elena Wachs is a trained tailor. In fact, the vest she wears on the day we meet was designed during her apprenticeship at Atelier Behrens in Hanover. Wachs is quick to praise the studio: “We were taught to shoulder responsibility from the very beginning, including mastering all pattern-cutting techniques, whereas in many other places tasks like making coffee and sorting needles were the norm [for trainees].”

Wachs, already a high school graduate at the time, was eager “to learn the fundamentals first” which led her to take on the apprenticeship. She then spent two years working at the costume department of the Staatstheater Hannover, where she was exposed to both conventional and experimental techniques. “We had to reconstruct patterns from historical illustrations because those templates and cutting techniques were unavailable,” she recalls. Marina-Elena—who also used to sing in a child’s choir at the same theater—quickly became captivated by the process, specifically how music was being translated into visual imagery, costumes, and stage presence. “I was fascinated by the entire production of it and the dramaturgy behind it. Whether it was assisting in the cloakroom or observing what was happening behind the scenes—I was interested in the wholeness of it all.”

Following the apprenticeship, Wachs further immersed herself in a flurry of activity, driven by her unstoppable pursuit of knowledge. She spent her third and final year of the “Gesellenzeit” (journeyman years) at Bogner in Munich before successfully passing the exam for the highest level of craftsman training in Germany, earning the prestigious title of master tailor. She then underwent pattern maker’s training in Hamburg, equipping her with the required skills to establish her own studio, which she did in 1994, specializing on made-to-measure fashion and costume design. (Here, she draws an interesting connection between design and architecture, pointing out that bespoke clothing is akin to crafting long-lasting and comfortable structures, a.k.a. “architecture” for the body.) In 1995, Wachs was among the 17 students selected from a pool of 600 applicants to pursue studies in Industrial Design at the Braunschweig University of Art—this decision stemmed from her desire to broaden her qualifications to other fields. Two years later, the impending arrival of her first son (her second son was born in 2002) served as inspiration for her pre-diploma project: a design for a delivery room. With a keen interest in space, Wachs had originally wanted to become an interior architect but was unable to secure a university placement at the time. She reflects on her journey: “I was always very curious. Thinking back on the last 35 years and all the things I’ve done in this time—that’s quite dizzying.”

It’s true, one might find it challenging at first to grasp the full extent of it all since her work is far from monotonous. Since 2010, Marina-Elena Wachs has been teaching Design Theory with a focus on fashion and textiles at Niederrhein University, while also striving to provide a practical approach for her students. As part of her studio work—which over time has developed into a space for research, feasibility reports, design projects (centering on material-development) and consulting—, she collaborates with Ulrike Brandi, lighting designer and founder of Ulrike Brandi Licht, and architect Ernst Ulrich Tillmanns on a project titled “Light goes”. For Wachs, working with people from different fields is highly enriching and a necessity. Together they research material solutions in design and light development. Wachs’ partnership with Brandi spans over two decades, originating from meeting at university, which we shall delve into later.

Wachs also conducts workshops for both corporate entities and children, is dedicated to what she terms “knowledge transfer”, meaning she publishes books to share her expertise, and offers consultancy services to ministries. In her role as a consultant, she also offers advice on material development (from 2003 to 2007 she examined the handling of materials in design, art, and architecture in her doctoral thesis Material Mind – new materials in design, art, and architecture): she evaluates and develops sustainable materials while also educating people on sustainable material behavior. But that’s not all. In addition to managing the demands of a full-time career and motherhood to her two sons, Wachs also cares for her mother and looked after her father until his passing in 2015. Listening to her extensive list of responsibilities (while I shamefully struggle to deal with a simple case of jetlag), I can’t help but ponder the many expectations society often poses on women. I find myself wondering: where does she summon the energy to do it all?

“Of course I need my own pursuits to regain strength. For me, that means traveling to France, immersing myself in nature, and experiencing a new language. It also involves music and sports, and I still take singing lessons,” she says. But there’s one aspect that perhaps surpasses them all: “Reflection. I believe it’s a deeply feminine trait—questioning oneself, harboring doubts—but it’s also a source of growth. It’s about learning which strategies to employ, when to assert oneself, and when to step back.”

A significant time in Marina Wachs’ life when she chose the latter was prioritizing the care of her sons. It’s important to note that she doesn’t perceive this choice as a “career hole”, although it might have been perceived this way from the outside at times. “At a certain point in my life seeing my son graduate was more important to me than attending a lecture by a famous designer. My male manager at the time would criticize me for it, insisting, ‘It’s your job; you have to go.’ To which I would respond, ‘Yes, it’s my job, but my children are my priority.’” While her ability to stand up for herself and her values is commendable, Wachs is also honest enough to point out that the time spent prioritizing family over work has resulted in a financial gap in her pension provision. “Prenuptial agreements were not common at the time, and women were not typically advised on how to navigate such situations. So, you have to balance this time out [afterwards]. Now that my children are out of the house, I have a better chance of doing that.” She continues: “But I don’t have to be in the spotlight all the time. It’s important to give the stage to the younger generation.” As a teacher, as we discuss, this means offering her students a platform to experiment and make mistakes without being punished for it. “It’s a way to rediscover a certain playfulness to approach things. With a naïve gaze—like we did as children.”

From when she was very young, Marina-Elena Wachs grew up building her “own kingdom”. She stubbornly tried to push through her interests in creative endeavors despite her parents, a post-war generation, envisioning a more secure profession for their daughter. Her earliest memories of creativity include her grandfather sketching Wilhem Busch’s Max and Moritz on grid paper; her grandmother, Meta Wilkening, who also taught her how to crochet, instilled in her an appreciation for beauty. Wachs remembers: “One Sunday, my grandmother, who typically wore an apron, put on a fancy dress and went to the hairdresser. She then picked out a huge bag from the closet, and, placing a travel ticket inside, took me to Hanover Park.” There, her grandmother bought her a slice of cake—an unusual thing for her to spend money on desserts—, handed her granddaughter a piece of paper and a pen before leading her to the rose garden to draw. “I will never forget the smell of the roses; the beauty around me was so different compared to the daily life that I was used to,” Wachs reminisces.

“Multisensory training in the formative years lays the groundwork for a holistic approach later on.”

Wachs’ grandmother originally hailed from Brelingen, a countryside area where her family cultivated flax in the post-World War II era. “They would harvest it, ret it, then scutch it before spinning yarn. Textiles would be woven using a loom; then monograms would be crafted.” One day, Wachs’ grandmother purchased a sewing machine and, by bartering 60 eggs for colored yarn, started fashioning clothing pieces for her children to wear on special occasions. It’s remarkable that the entire process, from harvesting the plant to designing the final clothing piece, was carried out by one single individual.

“This textile heritage that I have and the role that my grandmother and mother played in my life, I only truly understood the significance of it later in life,” Wachs reflects. In 2018, her grandmothers’ hand-stitched pieces were exhibited at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg as part of a participatory exhibition titled “Museum für Werte” (engl.: Museum for Values).

The key takeaway from this story is the importance of, as Wachs calls it, the multisensory experience, which derives from deep engagement with our surroundings and must be further nurtured in educational settings.

“Multisensory training in the formative years lays the groundwork for a holistic approach later on. Fewer businesses are willing to invest in hand crafts education, but it’s crucial to emphasize the need to retrain our multisensory skills (the tactile, the acoustic), as our hand-brain coordination is diminishing.” This, as Wachs later clarifies, serves a long-term purpose: “We need to generate knowledge for the so-called complex problem solvers who are able to see the bigger picture,” she asserts. “People often ask me about my background—working in textiles for more than ten years, then pursuing industrial design studies, and engaging in interdisciplinary work, I’m often told I do a little bit of everything. But I tell them, ‘no, I have a cohesive concept, I manage projects, and I delve into specifics when necessary.’ I always maintain an overarching perspective.”

Wachs further emphasizes the significate of interdisciplinarity in her professional approach. As a professor, she advocates for engaging in excursions with her students in order to seek opinions and perspectives from other disciplinaries, including architecture, that provide a distinct “didactic value”. These excursions to museums and special “places to remember” (filled with multi-sensual associations) are often followed by short sketching sessions, during which the insights gained are integrated into the students’ work. Despite teaching design theory, Wachs’ approach is highly participatory and integrates multiple forms of media, which is, in a way, her response to the world being highly dominated by “male ideals”.

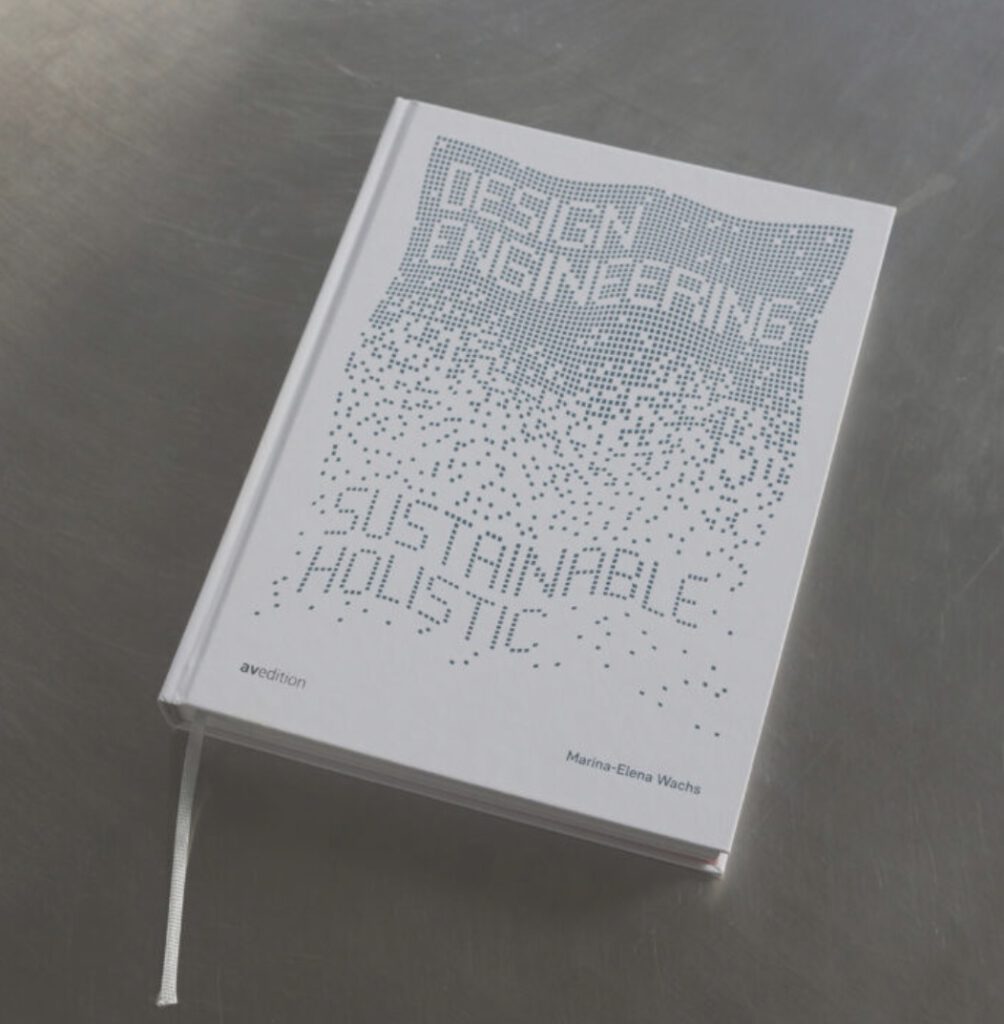

“In my generation, knowledge is power, and power is not something one wants to share. I think that’s horrible.” She addressed the issue of knowledge loss in her post-doc thesis Design Engineering – sustainable and holistic, outlining methods for creating knowledge archives, both personal and societal. “We should think bigger, more united, and more European.”

in 2022 with avedition. Photo: Knut Amtenbrink, 2022. Photo: Knut Amtenbrink, 2022.

To help tackle this issue, Wachs has established a mentoring program through her studio called PEM (Program of European Mentoring). Through this initiative, she provides young professionals aspiring to pursue a career in academia and research with a platform to enter this sphere, thereby fostering their visibility. As such, she puts an emphasis on self-management and encourages risk-taking and pro-active behavior. In the past, Wachs has invited Niederrhein University alumni to join her and present together at the Conference on Engineering & Product Design Education in Barcelona. For the upcoming conference taking place in Birmingham in September, she’ll be accompanied by a graduate from Germany and two new talents from the Netherlands and Denmark. “I am trying to facilitate the path for the younger generation because I wish someone had done it for me.”

Despite having to overcome her share of obstacles, Wachs says she’s been supported by many people, including women, throughout her life. These mentors include her aforementioned long-time collaborator Ulrike Brandi, who used to be a visiting professor at Braunschweig University of Art, where Wachs was studying at the time. They later collaborated for the 2010 Expo in Hanover, the first recognized World Expo in Germany under the theme of “Man, Nature, Technology – a new world emerges”. For this event, Wachs developed architecture and spatial modeling, including temperature-reactive seating elements that changed color due to polymers when coming in contact with a body. “[Brandi], who always challenges herself, used to tell me: ‘Remain persistent and friendly when pursuing a path, keep going, even after you have children.’” The advice must have struck a chord—Wachs’ tenacity throughout her career is undeniable. She also credits her mother and grandmother for embodying feminist ideals in their traditional households even if they couldn’t overtly express them to their husbands. Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, also makes the list because of her assertiveness in the male-dominated field but also for her fashion sense. “She has been able to maintain femininity and elegance in her clothing, unlike many other women in politics who may feel restricted to wearing pantsuits in order to be taken seriously,” says Wachs.

After this, as I try to dissect the broader meaning of femininity—or “the feminine”—our conversation takes a philosophical turn and inspires me to ponder the things discussed long after our interview ends. In our male-dominated society, where the ideal is often rooted in the rational, the feminine appears to be frequently overlooked. Wachs proceeds to say that the government invests increasing amounts of money in “the abstract, digital things,” neglecting the humanities. “We should not only encourage STEM subjects, the ones that are quantifiable and measurable,” she says. Because, in fact, the solution typically lies in the holistic, philosophical, and transdisciplinary approach. “Just consider design and architecture; you can learn so much from the metaphorical. Think Roland Barthes. Or Peter Zumthor and the impact his aunt’s garden had on him. How he recalled in his memory how the door handle felt in his hand when entering the garden, or the sound of the pebbles under his feet, or the gentle sheen of oak wood in the staircase. And that’s the question of embodied experiences…”

I think back to the beginning of our conversation when she shared her personal memories of drawing in a rose garden in Hanover as child, the fragrant scent of the flowers lingering in the air. How delicate this memory was and still is.

“… and the vulnerable,” I add.

“Yes, the vulnerable as well,” Marina-Elena agrees, then concludes: “Think crisis management. We cannot coexist with AI in the future if we do not have a humanistic approach to things.” This year, as one might expect, Marina will delve deeper into this topic and give lectures on “First embodied experiences before designing with(in) AI” at conferences in the UK and in Switzerland.

Hamburg 2021, thanks to Prof. Dr. Roland Greule. Photo: M.E. Wachs, 2021.

The multisensory experience, as I conclude for myself through our conversation, is the true origin of solution-based thinking. This is where passion and connection are born, and it’s crucial to nurture it from the very beginning by placing more value on the physical world. In our digital-dominated era, allowing children to play in puddles and mud, paint with brushes on canvas in the garden, work with wood blocks, singing aloud together while making music with stones—all the activities that Marina-Elena Wachs engaged in with her children when they were little—fosters our sense of empathy. It allows the feminine to flourish, and, hopefully, brings us back to ourselves, ultimately helping us to see the bigger picture.